*INCOMPLETE POST* Wrote this, and need to let it percolate. Check back in a bit for updates. I think there’s a lot of stuff in here I’m going to need to re-think. In the meantime, maybe you’ll enjoy this horribly long piece of technical tripe.

UNDERCOVER AiMer

Last month I attended a Postural Restoration Institute (PRI) course (pelvis restoration) with a simple agenda: I wanted to understand if the model of “gait” taught in PRI was the same as the Flow Motion Model (FMM) of gait taught in Anatomy in Motion (AiM). Are the mechanics and timings the same? Or are they working with different understandings of what is “ideal” to see in human gait?

Both PRI and the FMM have a way of viewing the “ideal” gait. What the “perfect” gait looks like- One we would want to help someone move more like in order to reduce pain and improve their performance. Nearly nobody will have an ideal gait, so it is theoretical to even talk about what is ideal.

If you have studied both with PRI and AiM, then you have likely asked yourself the same questions I have. So… For all 5 of you, this post is for you.

ONE YEAR OF AGONY

For the past year I had been trying to consolidate these two models, and it always left me feeling confused.

I had this feeling that, since they are both models working with the gait cycle, and both have a distinct feeling of “seeking truth”, they must be discussing the same joint actions and timings. I felt that If I could understand how the PRI model fit with together with the FMM, it could potentially open up a new world of understanding, using one method to inform how I worked with the other.

The way I saw it, was that the FMM was like a cup of tea with loose leaves floating in it- A seemingly disorganized pattern, but with all the answers floating right there waiting to be interpreted. The raw material. PRI, it seemed to me, could be what helped to interpret the leaves, as their main thing is pattern recognition.

The thing is, the models never seemed to line up no matter how hard I tried. As it turns out, the analogy above is likely to be yet another typical case of Volkmar-style naivete.

A LIBERATING AGENDA

That is, going into a CEU course without the the expectation that I needed to implement the information in my practice. Instead, I went in wanting only to understand the information presented, and compare it with what I already thought I knew. No pressure to use it or not. No stress about wasting peoples’ time tinkering with new stuff.

Generally, going into a course, my mind is set to “absorb and understand mode” which has four distinct components, involving listening understanding, retrieval, and reflection.

- Listen: Focus on the words the instructor is saying, make sure I actually hear them, not zoning out of thinking about lunch.

- Understand: A step deeper than listening- Make sense of the words and ask questions if I’ve failed to listen or make sense of what I’ve heard.

- Retrieval: A deepening of understanding- To immediately repeat internally, or back to the instructor/friend/stranger, what has just been understood, or write it down. This helps to learn it twice or thrice. This is also where things get a bit mentally intensive, as sometimes while I’m busy retrieving, the topic of discussion has moved along, and I’m trying to catch up on step 1 and 2 while still doing step 3.

- Imaginary application: A further deepening of understanding by relating it to my reality- Mentally reflect on how what I’ve just understood could be useful for me in my own practice, in real life. How does this relate (or not) to what I’ve done in the past? How can I use this in the future? How can I relate this to myself and my clients now?

But this time, going into pelvis restoration, my learning mode was was set to “compare” mode. The process is quite the same as above, but instead of the fourth step, there is a “comparison” step. And, in this specific case, my aim was to compare what was being said in Pelvis Restoration of PRI’s gait model with what I understand of AiM’s Flow Motion Model.

The result was very interesting.

THESE ARE NOT THE SAME MODELS

There, I’ve just ruined the whole post for you. But if you care about the specific differences, keep reading.

In a nutshell, the models of gait described by PRI and AiM are different. Different both in timing, mechanics, and in underlying philosophy. I’m not saying that one is better or worse that the other, but, will say personally, if forced to choose where I spend my time and continuing education budget, I must state my biased allegiance to AiM’s model.

Still, I feel tempted to study more of PRI. Logically, however, I understand that trying to consolidate two incompatible models may be a waste of time. Maybe… I will wait for someone to prove me wrong (really that would be great).

Well, let’s go through the differences why don’t we.

WHAT I LIKED ABOUT PRI’S PELVIS RESTORATION

As a biased AiM disciple, its worth stating that I really did enjoy the information taught in pelvis restoration:

- The attention to detail of the movement of the pelvis inlet and outlet. This was new information for me and I loved talking about the 8 degrees of movement the ilum, ischium, and sacrum have on each other it in such a specific way.

- The attention to respiration mechanics. I love learning about breathing, and, it was great to learn more detail about the pelvic diaphragm and “pelvis respiration”- how air flows through the pelvis in gait.

- That they relate the movements of the pelvis to gait. However, as I will discuss, I did not find that their model of gait could merge with the FMM. I just appreciate that they are relating what they do back to what I feel to be the most important, fundamental movements we do as humans: Walking!

AND NOW, THE GRITTY DETAILS

While PRI and AiM both claim to look at gait, they way they do it is quite different, beginning with their philosophies.

AiM’s philosophy I can summarize as such:

- Provide an experience for healing to happen and allow the body to experience new options

- Based on eccentric loading

- “Neutrality” exists only for a fraction of a second

- Tinkering is an important part of the process (“If things don’t go right, go left”)

- No assumptions, no stories, seek truth. If you look too hard for something, you might see something that isn’t there.

- Work with an ABA (test, intervene, retest) model, but don’t outright claim to be evidence based or objective.

- Find what’s missing, reclaim, take ownership.

- “We will give you everything we know in this one course”

- “We don’t have a certification”

And as I understand PRI’s philosophy:

- Put things back in the right position

- Based on concentric contraction

- Nothing can change until the body gets neutral, neutral is priority #1

- Systematic, flow-charted protocol to guide course of action.

- Look for an assumed underlying pattern (its there even if you can’t see it)

- Claim to be evidence based, ABA model with objective tests

- Reposition, retrain, restore.

- “To learn more, come to our other 7 courses”

- “You can get certified with us”

Again, I’m not saying one is better than the other, just that they are different.

As you could expect with such different philosophies, their methods and models of gait are also quite different.

After a year or so of trying to consolidate PRI’s model with the FMM, I finally have peace of mind. I can stop trying, because it is impossible: They are not talking about the same gait cycle! You cannot know what relief this was for me- It was worth the price of the course, for sure.

DISCLAIMER

Please keep in mind that my understanding of PRI is less thorough (having only been exposed to material from their three primary courses) than my understanding of the Flow Motion Model.

Further, my attempts to inquire at the pelvis course were stymied by the inability to communicate in the “same language” as the course instructor, which is as much my fault as hers. It is indeed difficult to speak about how the body moves when we see it through two different lenses.

The following is an outline of some of the main differences I noted between the FMM and PRI’s models of gait (I’m sure this is an incomplete list, and possibly, I have this all wrong).

Recall this comparison is not intended to make one seem better than the other, just to clarify the differences for those who may have been struggling to consolidate the models like I was. I have done my best to limit my biased language, but it was hard, because I am honestly, unashamedly biased towards FMM.

1. Whole gait cycle vs. partial gait cycle

PRI looks only at swing and mid-stance (as far as I know). To me, this is a shame as it is difficult to discuss what happens in mid-stance and swing without also considering what is impacting them (what comes before), and what they impact on (what comes after).

I find that PRI’s discussion of swing and stance occurs in isolation from the other phases of gait, which makes it very difficult to fully appreciate the role of some very important timings (we’ll get to that later). It’s like starting a book right in the middle and wondering why you don’t understand what’s going on and who the characters are.

So while PRI may claim that what they do is “gait”, our bodies do more than stance and swing. Perhaps they have a good rationale for this, or perhaps in the more advanced levels they get into the other four phases (suspension, propulsion, heel strike, and shift, in the AiM model, not to mention the inter-phases), but this was never alluded to, so I am not sure. This alone almost makes me want to take more courses. However, this seems like a cruel thing to do to a student- Withhold highly relevant information and provide an incomplete system to work with. I suppose there is money in that though.

Having been spoiled by looking at all phases of gait in the FMM, it felt somewhat neglectful to be considering only two phases with PRI.

2. Different timings and mechanics of mid-stance and swing

PRI’s midstance most strongly correlates, timing-wise, to the FMM’s transition, but with incongruent mechanics.

As far as I understand, in PRI midstance, these are some of the key mechanics:

- Hip extension, adduction, internal rotation

- SI joint open posteriorally, closed anteriorally (transverse plane)

- Foot is “neutral”

- Pelvic outlet flexing, abducting, externally rotating

- Pelvic inlet extending, adducting, internally rotating

This would be quite similar to transition but for frontal plane joint mechanics, and some other differences in timing (that we will get to later).

Firstly, the mid-stance phase in PRI cannot align with the FMM transition phase due to frontal plane reversal. What I mean by that is, in PRI, as the leg swings through, the stance hip is said to be adducted. However, in transition, the opposite is the case: The hip is abducting to neutral from it’s maximally adducted position in the phase just prior- suspension (foot flat).

In the FMM there are only three phases in which the hip is adducting: Suspension, swing (early to late), and heel strike. In transition, the hip is ABducting to neutral while the swing leg ADducts back to midline from an abducted position in the phase prior (propulsion). This frontal plane reversal throws the timing off completely from PRI’s model.

This is also a nice illustration of why it is useful to appreciate not only where the body is, but where it came from, and where it is going (partial vs. whole gait cycle).

At break, I attempted to ask the instructor a few questions to make sure I understand this. I thought perhaps in PRI they were referring to early swing, in which the hip would indeed be still abducted, but adductING to center, and the stance leg would still be adducted, but abductING. This could in theory make sense. So I asked, “Is this early or late swing?”. Her reply: I don’t understand where you’re going with this question. We’re talking about mid-stance.”

Ok, maybe I didn’t ask the right question. So I tried again, and used my body to show what I was talking about.

However, my questions were cut off when it became apparent that I was not speaking with a PRI lens. The instructor was quite distracted by the fact that I was talking about my left leg and not my right, trying to act out my words standing with my left leg back, not my right (it’s not about the left leg back in PRI!). I attempted to reverse my language and my legs to speak about the opposite leg (it really doesn’t matter which leg we’re talking about), and she proceeded to “correct” my positioning further rather than listen to my words.

Slightly frustrating, however, this led me to an important revelation about their timing of swing phase, or lack of consideration thereof…

The second large difference is one of timing of pelvis movement in transverse plane.

Both in stance and in transition, the hip is internally rotated. However, in the FMM, hip internal rotation happens in mid-stance (transition) due to the speed at which the pelvis rotates towards it as the leg swings through. The swing leg, being heavy and having a ton of momentum, pulls the pelvis into a rotation towards the stance leg faster than the femur of stance leg is rotating externally, creating an internal rotation on a supinated foot (usually, supination will result in hip ER, except in this case, for the reasons aforementioned).

So, in the FMM, internal rotation of the transition leg is entirely reliant on the timing of the swing leg and the speed of rotation of the pelvis. This can be confusing and difficult to explain to someone who hasn’t done the AiM course.

As far as I know, this timing is not present in the PRI model, and pelvis speed is not considered as contributing to transverse plane hip mechanics.

To further appreciate the implications of this, we must also talk about the types of muscle contractions each model is working primarily to influence.

3. Concentric vs. eccentric models

PRI views gait through the lens of concentric muscle contraction, as does the current anatomy/biomechanical paradigm. This is interesting when you consider the nature of gait as more of a controlled fall (as it is often described by those who look at it in the lab)- Muscles catching the body as it moves.

In terms of Gary Ward’s rules of movement (from his book What The Foot), muscles react primarily in this “catching” sense more so than in a concentric activity sense. He explains this with two concepts (rules of movement 1 and 2):

1. Joints act, muscles react, and,

2. Muscles must lengthen before they contract.

Viewing gait through these rules, we can see the importance of joints getting into positions which allow muscles to first lengthen in order to contract: A model of exploiting the muscular system’s inherent elasticity through eccentric load. Effortlessly. “Give the muscle no option but to contract.”

Catching, then contracting.

As the foot hits ground, for example:

- Foot pronates and supinatory muscles load (tibialis posterior et al) catch, and can then supinate the foot.

- Knee bends, muscles of knee extension (VMO, VL, etc.) load, catch, and extend the knee.In AiM philosophy, this is also how the “exercises” are coached- To feel the eccentric load, not force a concentric contraction. The mechanics of the FMM are also discussed in terms of what muscles are loading eccentrically at each moment in the gait cycle, not what is concentrically contracting.Having studied with Gary, I now view movement through this “catching” lens, and am definitely biased towards it, to be honest.

I once did a presentation (IADMS conference in Hong Kong 2016) in which I shared the idea of an eccentric gait/movement paradigm. There was one fellow in particular who could not accept that eccentric loading was the stimulus for muscle contraction. Is there proof of this? No. But…

But consider the graph below (taken from THIS STUDY):

Here, what we are seeing is the percentage of the people in a study who had EMG activity of various muscles at different phases of the gait cycle.

What is curious is that VMO, which we typically we consider as a knee extender (concentrically), is shown to be most active in the loading response phase before stance, which is a phase in which the knee is actually bent. Similarly, the hamstrings that are active in terminal swing will be in a long state due to the knee extending- this can’t be a concentrically contracting hamstring, yet still registers activity in 100% of the participants.

Why is the VMO contracting more frequently when the knee is bent than in mid-stance when it is straight? A muscle will have the highest contractile strength when it is lengthened (pull back an elastic band and feel the tension build the farther you pull it back) giving it no option but to then contract from that position. What are we measuring here? Is it the maximum pre-load before concentric contraction? Or, is it the first few miliseconds of concentric contraction while the muscle is still long? “When does a pendulum change direction?”.

The point is, what me may be seeing here is how the muscles that are eccentrically loading may be the most active on EMG.

Not that muscles don’t concentrically contract during gait, but measuring EMG with a pre-conceived notion that they contract at the highest output concentrically may be misleading. Also, it is highly likely that there are some flaws in this one study, and in EMG studies in general. Must further research this. Too, many gait EMG studies are done on a treadmill, which is not natural gait and not really even worth comparing to a ground-based gait.

Too, the information can be muddled as many muscles will be lengthening in one plane of motion, but shortening in another within the same moment in gait, and even at either ends of the same muscle.

For example, in heel strike, biceps femoris (based on mechanics of the FMM), will be:

- lengthening distally

- shortening proximally,

- lengthening in frontal plane,

- shortening in transverse(PRI peeps may argue about that, but remember, we’re talking about a different gait cycle).

We joke that Gary’s upcoming new book on the Flow Motion Model (coming soon!) should be titled, “The Confusing Book of Muscles”, or , “Fuck Muscles, Let’s Pay More Attention to Joints”.

In PRI’s approach, the body is taught to facilitate (or inhibit) muscles via concentric contractions. Their exercises reflect this and generally involve trying to generate concentric muscle contraction. Mechanics are explained in terms of what is contracting to create joint movement.

I am not saying one paradigm is better than the other (though I am making my bias evident). Both have the potential to work. But in my experience, and what seems to make the most sense, feels most natural, and has the greatest impact is to teach the body to respond reflexively to muscle length. This fits the fall-and-catch view of gait more accurately.

Personally, I feel that we shouldn’t need to actively squeeze muscles to walk. If someone has ever told you to squeeze your butt while you walk, stop listening to that person. Inserting concentric contractions consciously into gait will screw up the effortless flow.

4. Differences in timing of pelvis movement in swing phase.

As we’ve already discussed, PRI sees the swing leg have no (or little) influence on the transverse plane movement of the pelvis. Contrast that with the the FMM model, in which the swinging leg has a massive influence on the pelvis rotating in gait, which influences how the stance leg achieves internal rotation.

Let’s speak a bit more about the swing leg.

The general mechanics:

PRI: Flexing, abducting, externally rotating

FMM: Flexing, adducting, internally rotating (early), externally rotating (late)

Viewed through the lens of eccentric-based movement, where muscles respond by contracting to muscle length, what might cause the leg to swing? To answer this question with the FMM, we must look at what happens right before the leg swings to see how the swing leg is loading (to catch/contract).

Let’s consider the left swing leg. Before swing, the left leg is in propulsion (or late toe off), and the right leg (front) is in suspension (or foot flat, a pronation phase).

What is useful is the naming of the phases themselves indicate the function of that phase:

- Propulsion- Push the pelvis forwards onto the front leg, with the hip flexors reaching their maximum length as the hip extends behind the body. In fact, psoas loads eccentrically in all three planes here.

- Suspension- Absorb shock. The muscles of supination, hip and knee extensors, and spine flexors, reaching their maximum length.So, directly following these phases, the body has no option but to:

- Flex the propulsion hip (from maximum extension)= swing leg flies through like a slingshot.

- Supinate the front foot (from maximum pronation) = Supinatory response from the foot up through the body which pulls the pelvis into a right rotation.

The pelvis is further rotated to the right due to the momentum of the swinging leg, as the psoas catches from maximum transverse plane length.Too, in this pre-swing phase, the pelvis and ribcage have just reached the point at which they are maximally rotated in opposition to each other (pelvis left, ribs right), loading the obliques in the transverse plane, leaving them no option but to contract and switch directions of trunk rotation.

Or, this doesn’t happen if the body has learned to move more through active concentric contractions as a strategy, which can lead to overworking hip flexors, obliques, backs, and tight feet that don’t resupinate.

PRI’s view of swing is somewhat different. As I understand (and I could be wrong, but this what the instructor told me) first, the pelvis rotates to “neutral”, and then the leg picks up off the ground to swing. In this view, the movement of the pelvis happens more as a result of transverse plane muscle activity (glute med, adductors, obliques) contracting than due to the loading of the extended hip, and, the leg swing must surely be more concentric in nature, as rotating the pelvis to a “neutral” position loses some of the psoas load in the transverse plane. This makes sense for this model, however, as recall the swing leg is said to the ABducting and externally rotating, which I would interpret to mean that the psoas is not loading in frontal and transverse plane in the phase pre-swing as it does in the FMM.

In FMM what is most influential on the swing leg making its journey? Is it the rotation of the pelvis and strength of hip flexors contracting, or, the momentum of the swinging leg? While the resupinating foot rotates the pelvis, consider the size of the tibialis posterior (the psoas of the lower leg), compared to the psoas itself. Psoas is much bigger. Thus, the influence of the propulsion leg loading the psoas maximally pre-swing has a greater impact on the speed of the leg swing and the pelvis rotating than the resupinating foot could have on rotating the pelvis (which, again, is responsible for the transition hip internally rotating on an externally rotated femur).

Again, this is the FMM’s interpretation of swing mechanics, and, they take into consideration what comes before swing as important details. I also realize the paragraphs above will probably only make sense if you’ve studied the FMM.

Interesting to me how a shift from a concentric to eccentric paradigm can change timing so much. Interesting indeed.

5. Incongruent hip and foot mechanical coupling

This incongruence occurs during swing phase, to my knowledge, but also probably in stance phase, because in a closed system like the body, you can’t just change one thing and expect it not to change everything else.

What I am referring to primarily is that in PRI theory (yes, they will admit that despite their adamance for test objectivity and evidence based practice, their model is still theory), the swing leg is abducting with an everted foot. In the FMM, these two movements do not ever occur together. Well, they do, but only in a body that is not moving in a mechanically ideal way. In the FMM, to see an everting foot on an abducting hip indicates a problem, and is not what we’d like to see. In PRI’s model, this is a “normal” coupling.

What is similar between both models is that the foot in swing is everted. Sort of. In the FMM, the foot is technically referred to as pronated, not everted, as, even though there is less opposition between forefoot and rearfoot in an open chain, it still should be present. However, in the FMM, in late swing, meaning, anything after the “neutral” microsecond of mid-swing, the foot begins to supinate as the hip begins to externally rotate, BUT the hip is still adducting, even continuing to adduct through heel strike, reaching full adduction at the end of foot flat (suspension), one of two points in the gait cycle in which the foot pronates (not everts).

In the FMM, if the foot is pronated, this always must couple with hip adduction (though the hip may be internally OR externally rotating). In PRI, I cannot speak for their views on the rest of the gait cycle, but they seem to couple foot eversion with hip abduction. This may make sense in a bilateral stance while shifting the hips side to side (the foot of the side you shift away from will pronate while abducting), so perhaps this is how they arrived there, and this would make sense, however, gait is not a bilateral stance.

In the FMM, there is a moment when the hip is adducting with a supinated foot (heel strike/late swing), but never is there be a moment in which the foot is everting with an abducted hip, unless it shows up as a type two pronation in propulsion as a strategy adopted due to trauma, injury, or some other reason that would serve someone to avoid a more effortless way of moving.

Summary:

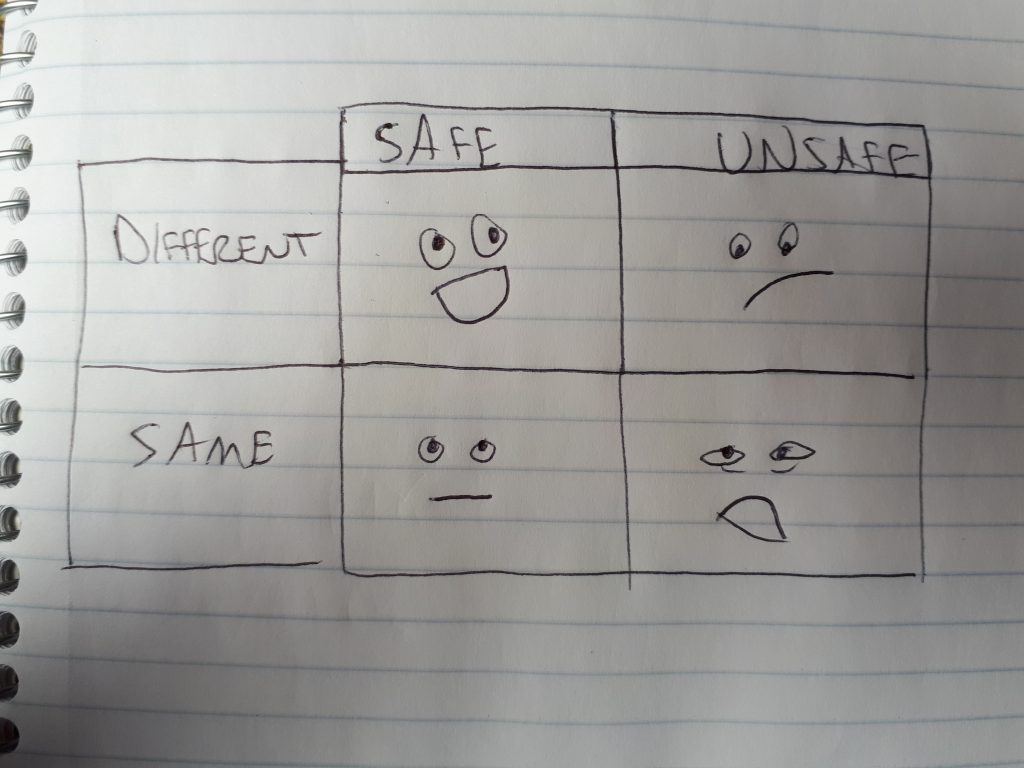

FMM:

Pronation + hip adduction = 🙂

Supination + hip adduction = 🙂

Pronation + hip abduction = 🙁

Supination + hip abduction = 🙂

(eversion and inversion are single joint movements within pronation and supination)

PRI:

Eversion + hip abduction= 🙂

Supination + hip adduction = 🙂 (their mid-stance, from what I gather)

An interesting note that I did not get to ask a question about but would have liked to: The instructor said something about “forefoot pronation and calcaneal eversion”. If you have taken AiM, then this will confuse you, as the FMM views pronation as a triplanar movement:

- Forefoot dorsiflexion, inversion, external rotation

- Rearfoot plantarflexion, eversion, internal rotation.

To say “pronation and eversion” makes me wonder about the differences between the two models’ foot mechanics. Maybe I should take their Advanced Integration course and find out…?

6. Different expectations for tri-planar joint couplings

In PRI, there are two primary couplings of tri-planar movement that we see over and over (a little too conveniently), which, for ease, are lumped under the titles of external rotation (ER), and internal rotation (IR).

For example, in this particular course (pelvis), we were told that when we are talking about ischio-sacral IR, what we also mean is extension, adduction, and internal rotation, but just use short-hand “IR” to describe it because IR always couples with adduction and internal rotation. The same is said at the hip. The swing hip, for example, is said to be in ER, or, flexion, abduction, and external rotation.

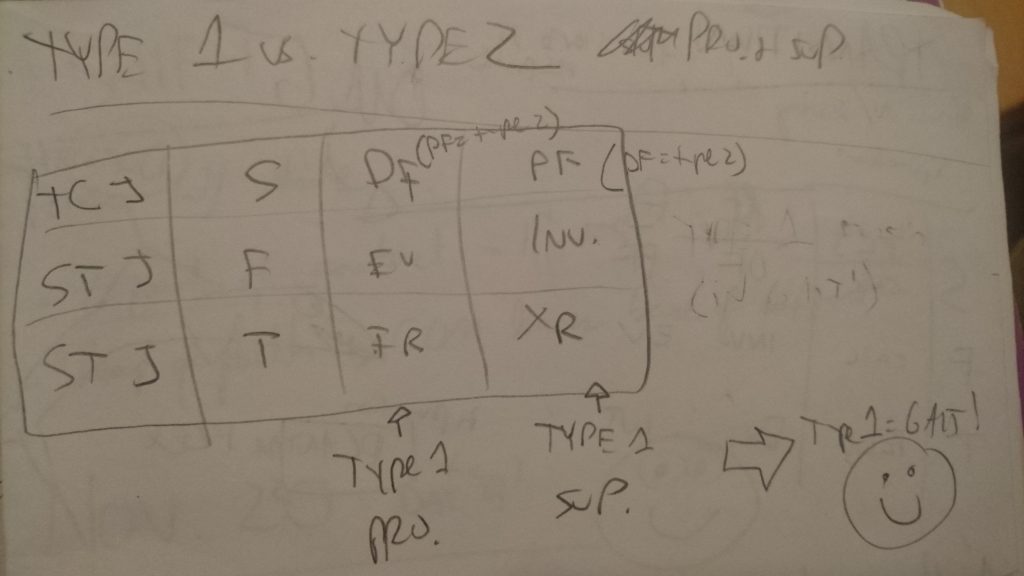

The rule per PRI:

External rotation (ER)= Flexion, abduction, and external rotation (swing)

Internal rotation (IR)= Extension, adduction, internal rotation (stance)

In the FMM, however, these couplings do not exist. Yes, the human body is capable of performing them, but they should not be present in the “ideal” gait we strive to restore, and are thus signs of inefficient movement.

For example, in the FMM, at the hip, we may see any one of these scenarios:

- Flexion, adduction, external rotation (suspension, late swing, heel strike)

- Flexion, adduction, internal rotation (early swing)

- Extension, abduction, external rotation (shift, propulsion)

- Extension, abduction, internal rotation (transition)

But none of the one aforementioned tri-planar couplings of the PRI gait cycle ever occur within the FMM… At least not at the hip. Perhaps elsewhere, but I am not sufficiently informed to make that statement.

7. To stack axially, or not to stack?

In gait, for greatest ease, our head should ideally be stacked over ribs over pelvis. For every bit the skull sits forward of the ribs and pelvis there is excess strain on the system.

Both PRI and the FMM describe that the movement of the skull and pelvis mirror each other in three planes, and the ribcage moves in opposition. Something to agree on! In the FMM this concept is called “cogs”, ie cogs of a clock which turn against each other to create motion. Many “exercises” in the AiM vocabulary encourage cog movement and, when possible, stacked axially.

In PRI this same opposition (cog) movement is encouraged, but is never (correct me if I’m wrong), in a standing activity, coached to be stacked vertically. Their appreciation of spinal opposition (yay) seems to be stymied by their exercises nearly always prioritizing a flexed spine position, often having the head forward of the rest of the torso.

However, not to bring this opposition into an axially stacked experience is limiting, as this is an experience the body needs to carry-over into gait. As we know, for every centimeter the head sits forward of the rest of the body, the strain on the muscles and the rest of the system will increase and alter movement mechanics. Makes sense to integrate the stacking as soon as possible, doesn’t it? I am biased, and, I’d like to think rational (mostly), so I will agree with my own last statement.

Personally, having witnessed the magic of the “wall-cog”, (a wall being used to provide sensory feedback of being stacked axially), and personally experienced how different it feels to perform skull, rib, and pelvis opposition stacked up, and will attest that it is an important detail.

Again, I’m sure the PRI world appreciates this, but is not mentioned in their primary courses. This, again, is the differing philosophies: “We’ll give you everything in this one course”, vs. “Come do the rest of our courses”.

CONCLUSIONS?

As I mentioned, I have an incomplete understanding of PRI’s model of gait, and many of the observations I’ve made may be rebuked should someone speak up and say, “Hey Monika, you just don’t know enough about PRI”. That is fair.

One question I am left with, as I was discussing with a fellow PRI + AiMer:

If their “objective tests” are based on a model of gait that is not the same as the FMM, can their tests (adduction drop test, etc) still be used as meaningful data to inform our intervention strategy? Not only for the FMM, but for any model of movement? The optimist in me hopes the answer is yes, but the skeptic in me does not.

For example, I have used AiM interventions and seen changes in PRI test scores (adduction drop test improvements). What does this mean if the models of gait are different? What changed? What am I even measuring?

I’m sure there is something value to explore there. I’m just not sure what that is yet…

That’s all I have for now. Congratulations for reading this far.

I admit, I am curious to continue to study with PRI, but, why study two completely different model of gait? Maybe when I’ve finished paying off my student loans and can be less frugal with my ConEd budget.

And lastly, there is a part of me that feels as if there must be something to what PRI claims about inherent asymmetry (organs, diaphragm, etc) contributing to predictable, patterned movement mechanics. It is intriguing and I am curious if, even though their mechanics are different, there is something useful to learn from their model.

To be continued…

Concurrently to this story about L, I was reading John Upledger’s The Inner Physician and You in preparation for taking the Upledger Institute’s craniosacral therapy level one course (stoked!). Reading this book was fortuitously timed, as I began to observe some of its main themes surface in my bodywork practice. In particular while working with L last week.

Concurrently to this story about L, I was reading John Upledger’s The Inner Physician and You in preparation for taking the Upledger Institute’s craniosacral therapy level one course (stoked!). Reading this book was fortuitously timed, as I began to observe some of its main themes surface in my bodywork practice. In particular while working with L last week.