A tale of navigating pain, with me, Monika. Our special guest for today is L.

L is one of my personal training clients. She is a badass 59 year old lady who has been slowly unwinding her body from a state of chronic pain over the past two years.

Last week she came into our session with a neck pain flare up. It hurt to tilt and rotate her head to the left. L usually likes to train hard, bust out push-ups (she can do 6 now!), and get a sweat going, but on that day she just wanted to be able to move her neck, so that became our focus.

Concurrently to this story about L, I was reading John Upledger’s The Inner Physician and You in preparation for taking the Upledger Institute’s craniosacral therapy level one course (stoked!). Reading this book was fortuitously timed, as I began to observe some of its main themes surface in my bodywork practice. In particular while working with L last week.

Concurrently to this story about L, I was reading John Upledger’s The Inner Physician and You in preparation for taking the Upledger Institute’s craniosacral therapy level one course (stoked!). Reading this book was fortuitously timed, as I began to observe some of its main themes surface in my bodywork practice. In particular while working with L last week.

The aforementioned themes, fresh in my mind from reading Upledger’s book, that seemed to over-arc this session were:

- The individual is his/her own healer

- We all have an “inner physician” and “censor”

- Until the “root cause” is identified, the same symptoms may keep returning

Nothing new, I know. But sometimes these truths don’t sink in until we’ve had enough experience of them. The timing of L’s neck pain was a gift to me in order to better explore these themes in real life.

How do you even shoulder-check?

L’s neck pain had been present for a long time at a low level as general stiffness, but last week when she came in it was bad enough that I wondered how she had even been able to shoulder check as she was driving over to see me.

As a side note, the thought occurred to me the other day: How many car accidents are caused by people with left side neck pain who can’t shoulder check?

I asked this same question to a client of mine a few years ago, “How did you even drive here if you can’t move your head to the left?” His answer, “I don’t need to, I drive fast…”. Please don’t be this guy. Take care of your body and be less of a danger on the streets.

Anyway, back to L. Her history.

When I first met L she had two bad knees (one had been operated on), thought she was going to need a cane to walk, couldn’t sit cross-legged because of her painful knees, and couldn’t lift her arms over her head due to shoulder pain. You could say she’d gotten her body into a bit of a messy spot.

Today, L can squat, lunge, sit cross-legged comfortably, lift her arms up and hang from a bar, and best yet, can do 6 full push-ups. She’s come a long way.

The main issue that initially brought L in to doing sessions with me was her right knee. She’d had surgery on it when she was 19 and, like any normal 19 year-old, she didn’t put a lot of thought into the recovery process.

A few weeks ago I asked her how she’d rate the care she received for her knee, and she said, “I was 19… So. Yeah. That.” Like most of us at that age (or at any age, let’s be honest), she had probably rested until the pain went down enough to start walking on it again without a lot of value placed on doing any sort of rehab exercises to regain full motion at the joint.

If the symptoms disappear and you can get around well enough, no more problem, right?

And then if you develop neck pain 40 years later, it’s probably not related, right?

I will admit now that I too am guilty of this way of thinking in my previous work with L.

I ignored a problem

Very shortly after L and I began working together, her knee pain stopped. It was that dang Anatomy in Motion stuff– It really simplifies how to work with knees (and the whole body, really).

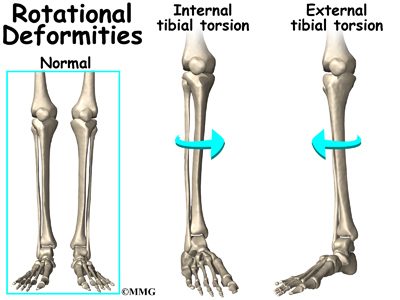

After her pain disappeared I reassessed her knee and saw there was still a movement issue: Her knee was stuck in an externally rotated position (tibia pointing out farther than femur), and her knee seemed to not have any transverse plane movement when she bent or straightened it (which we should be able to see and feel in a healthy knee).

But because her symptoms were gone, and any time we tried to feed what I felt to be “appropriate” movement into her knee, it felt painful. So, like any trainer who doesn’t want to lose a client because we keep doing stuff that hurts, I decided to ignore it. And we did that for a year without her complaining about her knee again. I thought this was good, and that the problem had taken care of itself.

Until last week.

Time doesn’t heal, healing heals with time.

Can we experience healing without pain?

Here we see surface an intriguing point of learning from Upledger’s Your Inner Physician and You. Upledger described several phases of an acute healing process. He describes, in his hands-on work, a “therapeutic pulse”, a “release of heat”, a temporary increase in the pain, and then relief from it. He says that this increase in pain is a part of the process, and it always subsides if the work is brought to completion correctly.

This has me wondering, what if, in the moment of doing the appropriate healing work, the increase in symptoms is necessary? When I stopped moving L’s knee because she reported pain, was that something to move into or away from? Healing or dangerous?

If it is true that a temporary increase in pain is part of the healing process, yet many of us avoid moving into a problem because it temporarily hurts, it is no wonder that we get ourselves into increasingly messy spots. We choose comfort over truth and deny ourselves freedom and ease.

But of course, it is hard to know whether this is true. Upledger was describing craniosacral work which is a gentle manual therapy. Does the same apply for movement?

Of course I mean moving gently, patiently, mindfully an area of the body that is experiencing an issue produce the same healing effect as holding it and waiting, with the same patience, for the area to release itself? If I start to move an area and feel pain, should I stop right away? Or is this a cue that I am initiating a healing process and would be doing myself a disservice by not bringing it to completion, fully exploring it.

I suppose this is something Upledger might say the individual intuitively knows the answer to in the moment, if we take the time to inquire.

Whatever the answer may be, I think the experience of pain is always a nice opportunity to open a discussion about the change/comfort matrix.

Change and comfort matrix

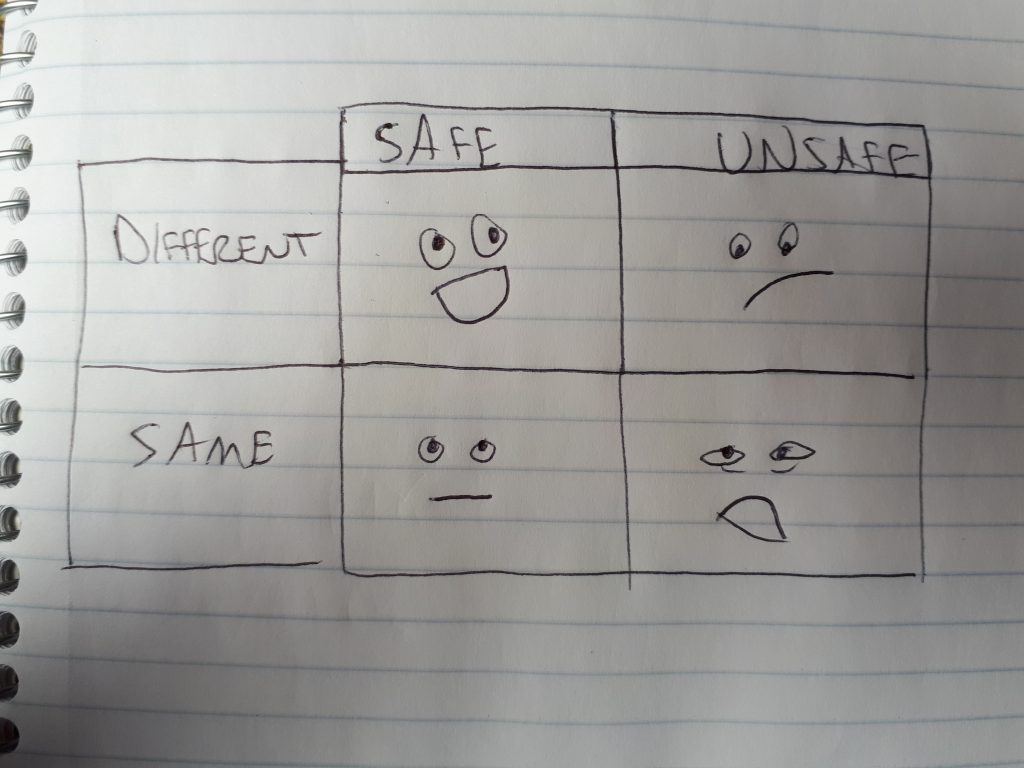

I think that all movement (and life) experiences fall into one of these four quadrants (in which “unsafe”, in the body, generally equates with pain or doomy apprehension, and “safe” is the absence of pain and a sense of comfort).

Safe + different= Where you want to be exploring (no pain, but maybe unsteady, awkward, challenging, shaky due to it being a new experience)

Safe + same= Staying in the comfort zone (no pain, no challenge, no change)

Unsafe + different= A new may of moving that triggers a threat response (painful, unsteady, awkward, challenging, fear provoking, activates sympathetic nervous system, and no lasting change)

Unsafe + same= Staying in the (not so comfortable) comfort zone (painful but no more painful than what we’re used to so it feels “normal”, moving habitually, no change)

Perhaps we just need to stay with a new input (movement, manual therapy, idea) for long enough to make the transition from unsafe/different to safe/different, because any new input to our nervous system may initially be perceived as dangerous, whether it really is or not.

Just some thoughts on navigating pain that I’ve had lately…

Pattern recognition

So anyway, here I was with L, feeling like I had no idea what we were going to do, plan for today’s training session out the window.

We had tried a number of movements that usually help get her neck and spine moving as part of her warm-up, but everything hurt too much to do, so we aborted mission.

From Upledger’s book, another theme presented itself: Treat the body on each day as if you are assessing for the first time. Try not to be biased by how the individual was last week, what other people have “diagnosed”, or even what the individual says about it. These stories may not apply to today.

And in that moment when zoomed out I was able to recognize a pattern.

In Anatomy in Motion (AiM) we assess the whole body in terms of phases of gait- What each joint does and when it does it as we walk. Each phase has it’s own signature shape, or pattern which we can begin to recognize in ourselves and others.

In the AiM Finding Center 6 day immersion course we are trained to understand what should be happening within each pattern at each joint in the body at any given moment in time as we walk.

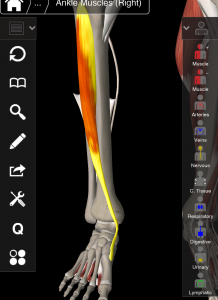

L’s head not being able to tilt or rotate to the left was part of the same pattern in which, at the same time, her right knee should be flexing (we call this pattern “suspension phase”, more commonly known as foot flat). Since I knew, historically, her right knee had movement limitations, I wondered if the position of her neck was the result of an exchange within that pattern over many years of adaptation around a problem.

If the pattern can’t be completed by one joint (the knee), we see this phenomenon called “exchange” in which another structure will try to accommodate for that.

Exchange: If we can’t fulfill a lack (missing knee motion in this case), we will look somewhere else to fulfill it (perhaps at the neck?). This happens at all levels in our lives. When something is missing, we find other ways to fill space, whether they are the healthiest for us or not, whether we are conscious of it or not.

Had her neck become a solution for her knee that became a problem of its own?

To test this knee/neck relationship, I had L simply stand with her right knee bent while testing her painful neck ranges- They immediately improved in range and felt less painful. Not perfect, but better.

You should have seen the look of L’s face when I said, “I think your neck issue is because of your right knee”. Like I’m a crazy person.

For those who have already taken AiM or are interested in the biomechanics of this, these are the mechanics I observed when I reassessed L’s right knee:

- Tibia anteriorally tilted (top of tibia tilted forward under the femur)

- Knee externally rotated (tibia rotated laterally of femur)

- No further movement into external rotation as the knee flexed (we should see the knee externally rotate as it bends)

If you haven’t taken AiM or don’t give a shit about biomechanics (unlikely, if you are reading this…), what this means is her knee was stuck in a more “bent” position in both sagittal and transverse plane, and couldn’t access any more bend, it already being there, bent.

The strategy, in my mind, seemed to be that we ought to show the knee how to extend and internally rotate, or more specifically, get the tibia to posteriorally tilt and internally rotate under the femur. Doing this would help it find a more centered resting spot allowing it somewhere to go when she bends her knee, rather than hit a block, and in theory, this would relinquish her neck of its excessive role in the full body pattern.

Using two movements from the AiM toolkit we explored ways of getting her knee to experience the above movements it was missing, and then integrated that up through into her neck as best we could.

L was mindful that the sensation in her knee felt different, and vaguely unsafe. At that point, we had a nice discussion of the comfort/change matrix. Fortunately, L trusted in the thought process I had explained to her, and after a few more moments of gently feeding movement through her knee, she reported that she was in the safe/different quadrant (is trust the anathema for feeling unsafe?).

When we finished, she stated that something definitely felt different about her neck, though she wasn’t sure what. She tested out her painful neck ranges, and they had improved. Not perfect, but on the right track.

Someone’s elses’ limiting beliefs

After this exploration, L told me an interesting story.

Apparently, when she had gone back for a consultation from a sports medicine doctor about her knee years after the operation, she had been told that she would never have full function of her knee again. She wondered aloud, “Have I been unconsciously limiting my potential because of something a doctor told me years ago? Something that wasn’t true?”. She didn’t question this statement at the time, that her knee was doomed never to work again, because he was the doctor. She seemed genuinely fascinated to understand how lifting this limiting belief could liberate her body from pain.

Let go of the handbrake

At this point I brought up the idea of the “handbrake” to the system- That we can try to teach the body to move “better”, but if there is something getting in the way (usually something from an injury history), then nothing will change because the brake hasn’t been removed.

Part of our job, as explorative movement facilitators (I am going to put that job title on my business card), is to find what’s getting in the way of people moving well, and then trusting that the individual’s own, intelligent system will be able to do the healing itself.

Another theme that surfaced from Upledger’s book: We are not healers, we are holding space for the body to heal itself.

I cannot be so arrogant to presume that I know what is best for someone’s body, life, mind, whatever.

All I can hope to do, and perhaps what is the highest form of healing, is to have the intention simply to be with somebody through their process. To listen before asking. To be present with them. Explain my thought process so that they have the option to trust it.

This is not a relationship between the healer and the broken, but a relationship between equals.

Priming the system

I also explained to L that other movements and stretches she can do directly for her neck are still good. The are ways of priming her nervous system for healthy ways of moving once the handbrake is removed.

By priming her nervous system with general movements, we are making future options for neck movement more familiar, more recognizable for her body to perform, once she has dealt with the thing that got in the way of it all to begin with.

And that brings me to…

The things that get in the way

I am reminded of a talk I listened to recently by Brene Brown, titled The Power of Vulnerability (listened to it twice in a row, strongly recommend), that mirrors this discussion.

To introduce her talk, Brown tells a story about a speaking gig at which she was expected to present on fluffy things like, how to be happy, how to be successful, etc. But as a shame and vulnerability researcher, her area of focus was “the things that get in the way”. The things people don’t want to talk about because they are hard and raw and most of us don’t want to go there.

It’s well and good to tell people how to be happy and successful, but how many people can actually take action on “happy and successful” until they’ve dealt with their own handbrakes? Shame, fear, and vulnerability. The unsexy stuff.

In the movement, personal training, and rehab worlds, we have plenty of people showing us how to move well (happy and successful), but not enough people talking about the things that get in the way (the handbrakes to the system).

There are literally thousands of resources that can teach you how to squat, deadlift, handstand, improve your “bad” posture, do yoga, “fix” your flat feet, etc. but hardly anything that can show you how to navigate the roadblocks. I think this is because 1. it is such an individual thing that it is hard to make a guide on, and 2. Becaues most people don’t think about “what gets in the way”, they just want to jump right into “happy and successful”, and “happy and successful” sells a hell of a lot better.

One of my teachers, Gary Ward, founder of Anatomy in Motion, has created an online resource that I think is the closest yet to removing the handbrake without actually working with a practitioner in rea life. His movement exploration is called “Wake Your Body Up”. <—Check it out.

The inner physican

Upledger describes in one section of his book that we have inside us an “inner physician”, and a “censor”. The censor has good intentions (safety!) but is the one who is skeptical about everything, who calls bullshit and can put a block in the road of healing. The inner physician opens a dialogue for healing, for finding the root cause of an issue and exploring, and asks us to trust the process.

L is in touch with her inner physician. She left inteigued to explore the work we did, intrigued by the thought process behind it. To her, it made perfect sense. As Upledger wrote, our bodies have an intelligence of their own, and if we open that dialogue with our own inner physician, we will find that we intuitively know what the problem is. Just have to pay attention…

Conclusions?

L’s homework was to practice moving her knee (safe/different) a few times a day using the movements we explored- remove the handbrake (stuck knee) and give the body a chance to heal itself.

I am grateful to have had this experience with L, and look forward to continuing this process with her.

I am left thinking, we always get what we need from life. Did L experience a neck flare up because she needed to address her knee? We’ll see what happens.