I recently began working with a very talented professional singer/vocal coach we’ll call Louise (not real name). Her primary goals were to improve her health, movement quality, and strength, aka, my favourite kind of person. She also enjoys geeking out about breathing and her super interesting feet, which makes her my very favourite person right now (not that I play favourites….).

We’d had a good chat about breathing before our first session (my fascination with it, her need to have good control of hers for her profession), and so I was particularly curious to see what her breathing habits were like, among other things.

A few interesting things have come up in our work together so far that I’d like to share as I attempt to make sense of the relationships between breathing, spine, and larynx mechanics in my head.

Belly breathing vs. “ideal” diaphragmatic breathing pattern

I would imagine that singers pride themselves on having good diaphragmatic control, but, much like Tiger Woods’ swing, there is much that can be improved upon mechanically even if you perform at a high level and kick ass already.

Louise is very good at using her diaphragm as a breathing muscle, but, and this is a big BUT, she uses it at the expense of maintaining any tone through her abdominals, which shows as a belly-pushing-out breathing pattern rather than an “ideal” diaphragmatic breathing pattern that could create greater intra-abdominal pressure (IAP).

Belly breathing IS diaphragmatic breathing- The abdominal excursions with inhalation are due to the diaphragm descending (contracting), but, the belly moving forwards, and only the belly, is indicative of the contents of the abdomen moving forwards without abdominal or pelvic floor eccentric co-contraction. This forwards movement is not going to be the best way to create “support” through the midsection, both for singing and strength training.

An ideal diaphragmatic breathing pattern involves, upon inhalation, both the belly and chest moving anteriorally, a posterior lateral expansion of the lower ribcage, and the pelvic floor descending as the organs are pushed down by the diaphragm. Not only the belly moving forwards.

A nice way of visualizing it is a 360 degree expansion of the thoracic (ribcage) and abdominal cavity, much like an umbrella opening, or a balloon blowing up. The balloon doesn’t just expand on one side, unless it’s a fucked up balloon.

If the belly/organs are pushing forwards, it is likely because there is no room for the abdomen to expand to the back (posterior-lateral expansion), and the pelvic floor down (descending), and so the only place for the organs to move is forwards (not ideal).

The excursions of an ideal diaphragmatic breath will appear to be smaller than those of a belly breath. Part of this is due to the abdominal fill being redistributed in a 360 degree fashion, and air flow also expanding the upper ribcage and subclavicular space, which creates a more evenly distributed fill, rather than the prominent belly breath. This “smaller” fill (volume of air) with the more ideal diaphragmatic breathing pattern will initially feel as if you are not getting enough air. This may be simply because the fill shape feels different and freaks out the nervous system, but could also be because belly-breathers often breathe in excess of metabolic demands (see G: Gasping for Air), whereas an ideal diaphragmatic breath will get more oxygen with less total air volume (let’s not go down that rabbit hole today…).

The posterio-lateral expansion that allows for the 360 filling can only happen if the abdominals (transverse abdominis- TVA, and internal obliques- IAOs, primarily) stabilize the ribcage: Eccentrically loading to slow it from lifting up and flaring excessively and the belly from pushing forwards.

Needing to counterbalance the organs being displaced forwards, belly breathers tend to get pulled into lumbar extension pretty easily (I would know, because I’m a recovering compressed-spine belly-breather), which makes it even more difficult to maintain any abdominal tone with inspiration due to the lengthened state of the abs, and compressed state of the spine.

To summarize, a belly breathing pattern does use the diaphragm, but not as effectively as it could, as the abdominals are not doing anything to generate internal pressure and muscular support. The big movement of the belly means that:

- Minimal expansion of the thoracic cavity will not decrease the intra-pleural pressure as much, meaning that the lungs will not fill as deeply and efficiently with each breath, reinforcing the need to take bigger belly breaths to feel like the lungs are filling “enough”.

- It will be more difficult to create pressure within the abdominal cavity (IAP) due to decreased TVA, IAO, and pelvic floor support, the foundation for spinal stabilization with movement and, importantly for Louise, support while singing.

I believe it will be useful for her to train herself out of the belly-breathing pattern and into a one that uses more abdominal co-contraction.

Training to hold onto an “air reserve”

In other words, training to create a functional hyperinflation just in case the need for more air should arise while singing. I can understand how holding onto a “reserve” would be useful if you have a long phrase or note to hold, or you accidentally neglect to breathe at the most effective time and need to push your air a bit further.

But there is a consequence to this, as training to hold on to extra air over months or years can have the effect of creating a more chronic hyper-inflated state- Excess air in the lungs, diaphragm and ribcage stuck in an inhalatory state, with an inability to completely exhale.

Why is this an issue?

Over time, hyperinflation alters the position of the ribcage, and puts the diaphragm in an even further disadvantageous position to breathe from: A state of perma-semi-contraction (that’s a word…).

Louise noted that she has a difficult time exhaling completely in our breath work, and would quickly feel the urge to breathe in deeply. She struggled to get her ribs to move down and in to an ideal zone of apposition (ZOA), or exhalatory, depressed (anteriorally tilted) rib position and breathe without flaring up her ribs with each inhalation (which would lose all IAP, aka “support”).

Because the diaphragm lengthens and ascends with exhalation, when more air than necessary remains in the lungs over long periods of time, it can become difficult to get diaphragm to get to a fully lengthened resting state. Because muscles must lengthen before they can contract, this makes an ideal diaphragmatic inhalation near impossible, spinal stabilization difficult, and compromises IAP generation.

Holding a “reserve”, or, a functional hyperinflation, does make sense as an adaptation to her “sport” of choice. However, if left unchecked, it will keep her from using her breath as efficiently as she could be, as being stuck in a perpetual semi-inhalatory state impacts on her quality of both inhalation, exhalation, and internal pressure regulation. Perhaps this is a deeply ingrained part of the singing training tradition; much like passively overstretching is part of ballet training tradition- Practices that can lead to compromised performance, but no one is taught a better way of doing things.

Here is some excellent art by me, illustrating some of the silly “traditions” I ascribed to as a dancer:

Louise and I discussed that owning the full spectrum, i.e. full inhalation and exhalation, rib flare and ZOA, diaphragm contracted and relaxed- would help her to find a more “centered” place with her breath and body, and decrease the reserve of air she needs to hold on to, which would decrease the chronic hyperinflation over time. Doing so would also help her to fill her lungs more efficiently and better use her diaphragm for it’s spine stabilization function, creating higher intra-abdominal pressure, which will come in handy when she needs the support for singing the higher tones without going in an “airy” head voice.

As an inexperienced singer, my thoughts are that the reserve training is probably useful, but the minimum possible amount of trained hyperinflation to get the job done is desirous.

The reserve is similar to packing for a long hike: You want to pack as little as possible to make reduce the weight you’re carrying but not starve. Hiking without a bag at all would be ideal, but not realistic (unless you have someone trailing you with your food and water supply in a helicopter).

After the hike, you can take the bag off and unwind, and, after singing and over-breathing a bunch, it is also a good idea to unwind.

Another important thing to note is that, if Louise does try to sing with the breathing patterns we are discussing as more “healthy” physiologically, she may experience a temporary decrease in her singing abilities, which, may not be desirable if she has to perform. This is comparable to taking away an athlete’s functional adaptations. For example, if a dancer needs a lot of flexibility in her hamstrings, and stiffness in her feet, and we take this away because it is not “healthy”, she may suffer a decrease in her dance technique. Similarly, if we try to make a sprinter too mobile, they will lose the stiffness which is in part necessary for them to generate power and speed.

There is a sweet spot, which, I believe exists within the exploration of the spectrum: Can you inhale and exhale? Can you play at the extremes without losing sight of “center”? And can you play with the bits in between without losing sight of the edges?

Ultimately, I believe that working on the diaphragm + abdominal control, deeper more efficient filling of lungs, and being able to exhale more fully will provide her with more options for how to use her breath, and more opportunities to unwind from the stresses that singing can have on the body.

Stiff spine and effect on larynx control, tone, and pitch?

Degree of spinal mobility and neck positioning can have an impact on, and be impacted by, breathing and ability to use the larynx effectively (and visa versa). This is something I am just starting to put together, and may need to revise this section later. Bear with me now and please correct me if I’m wrong.

Louise is stuck with a fairly flexed thoracic spine that doesn’t know how to extend, and a extended cervical spine that doesn’t know how to flex. As a strategy to extend her thoracic spine, Louise retracts her scapulae together excessively in an attempt to create spinal motion, a common strategy for stiff spines that I frequently see.

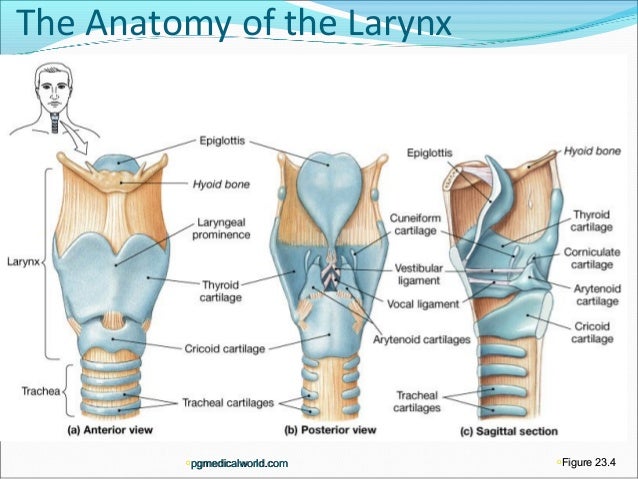

For singers, being able to flex and decompress the C spine is necessary to modulate the quality of their voice. This is due to the larynx, which houses the vocal folds, being located around level C3-C6.

The larynx is suspended from the hyoid bone, which is what Gary Ward (author of What the Foot) has classified as a “dangler” (technical term). This means that its gross movement is primarily due to the movement of another proximal structure (for example, scapulae are also danglers, suspended on the ribcage, the jaw is a dangler, suspended from the cranium). In this case, the hyoid is closest to the cervical spine and skull and so hyoid, and thus, larynx, movement can be mapped based on C spine and skull movement.

The hyoid also has a pretty cool connection to the scapulae via the omohyoid muscle (which I just learned about yesterday). This means that there could be some tricky strategies going on between Louise’s hyper-retracting scaps, stiff spine, and hyoid/larynx, that may have an impact on her voice.

Another thing worth noting is the the closing of the glottis to increase sub-glottal pressure, sometimes known as the Valsalva manoeuvre. This allows greater building of air pressure to stiffen the abdominal cavity and is useful to protect the spine for higher threshold activity, like lifting heavy things, but also at lower thresholds it serves to stabilize the spine during simple limb movements. Some people may tend to overuse the muscles of the hyoid/larynx to create this stabilizing pressure rather than being able to use their diaphragm and abdominals (TVA + IAO) effectively for IAP, which can mess with the larynx’s role in air pressure modulation and resultant vocal quality.

For someone like Louise who does not use her abdominals effectively to create IAP (as a belly breather), she may be overusing her hyoid and larynx musculature to create it, or, locking into bony end range at her C spine, in an attempt to create a sense of stability, which will impact on how well she can also use her larynx to modulate her voice.

What all that means is that one’s potential vocal range and ability to modulate pitch and tone is somewhat dependent on spinal mobility, internal pressure regulation, scapulae movement, as well as freedom of hyoid movement (to dangle).

Where things get interesting is when we look at how larynx movement can affect pitch and quality of the voice:

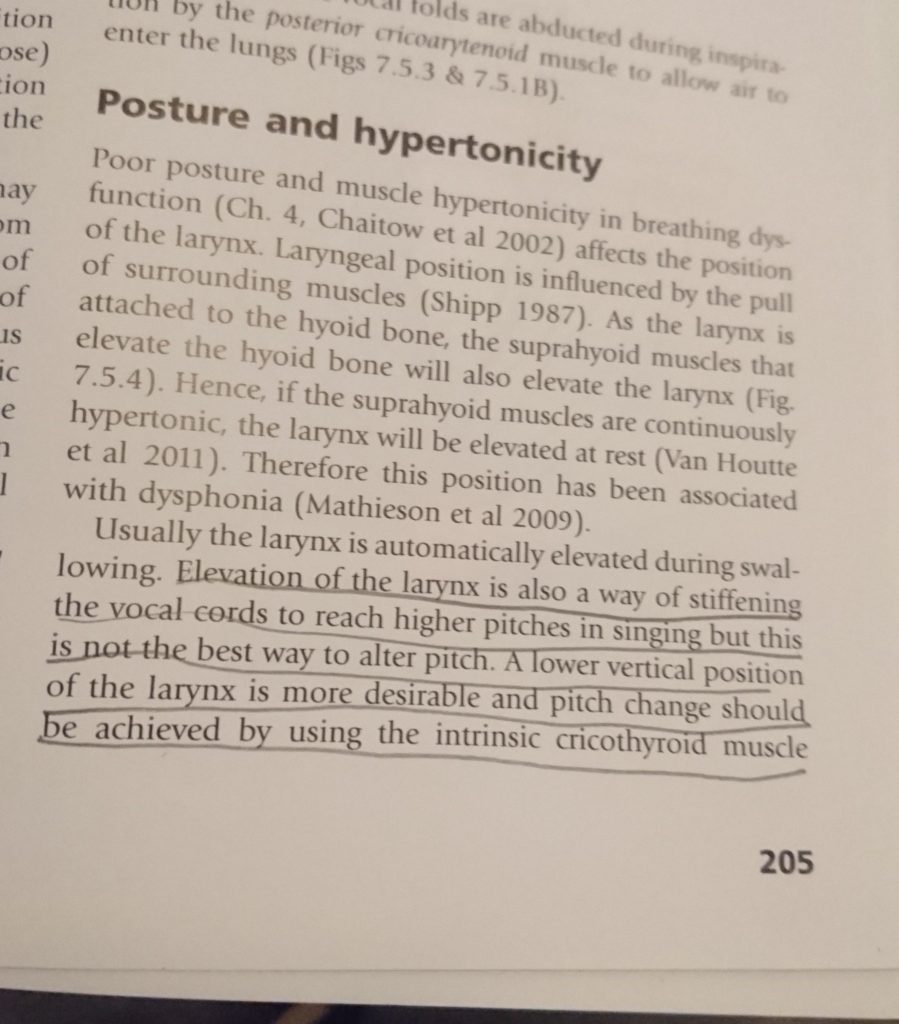

- Larynx elevation = higher pitches (stiffens vocal folds)

- Larynx depression= lower pitches

- Larynx anterior tilt (forward over cricoid)= higher pitches (lengthens vocal folds)

- Larynx posterior tilt= lower pitches

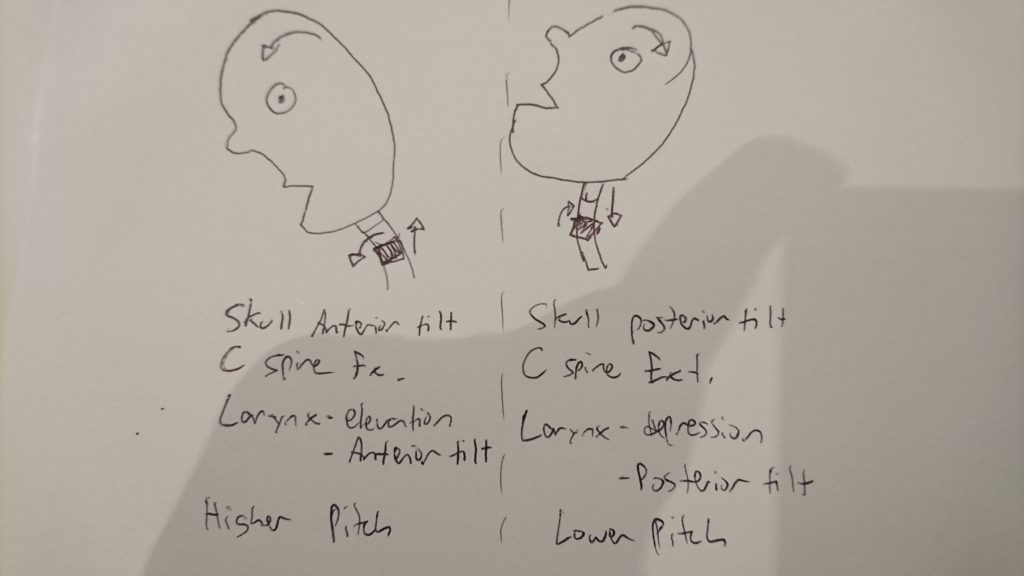

To correlate this to C spine and skull movement:

- Skull anterior tilt + C spine flexion = larynx elevation + anterior tilt=stiffer, longer vocal folds= higher pitches (also opens airway)

- Skull posterior tilt + C spine extension= larynx depression + posterior tilt= lower pitches

However, as Louise has explained to me, the movement of the larynx may have more to do with the quality of the voice, regardless of the pitch, due to how it modulates air pressure. A higher larynx will tend to raise the air pressure and make the quality of the voice less airy, and so is useful for getting high notes to sound less “heady”.

Here is yet more excellent art by me:

When the larynx tilts forwards over the cricoid (anterior tilt) and raises, this lengthens and tenses the vocal folds to create higher pitches. However, altered neck position and resultant muscle tensions can limit this anterior tilt.

Here’s where things get more fuzzy for me. I have read that relying on moving the neck and skull to move the larynx is not as effective as being able to use the intrinsic muscles of the hyoid itself to move the larynx to modulate pitch and volume.

A lower resting position of the larynx is said to be more desirous and healthy than an elevated one. I suppose this makes sense as this means that should one need to push into a more headier voice, there is actually somewhere for the larynx to go. However, I would also reckon that too low is not great, especially if stuck there. Like any other structure of the body, I suppose the holy grail is to find “center”, and to do this we must also know the extremes.

When it comes to using intrinsic muscles of the larynx, I am not entirely sure how to train this because I’m not the one who’s a vocal coach with the experience in that domain. However, I can imagine that unlocking the neck and spine mechanics, breathing mechanics, and ability to co-contract abdominals, diaphragm and pelvic floor to create IAP will free up the muscles of the hyoid and larynx to perform their vocal manipulatory role more effectively, which will have a spill over effect into vocal training.

Here’s what’s currently going on with Louise:

- C spine stuck extended= Larynx stuck in posterior tilt (potentially)

- Skull stuck in posterior tilt= Larynx descended (potentially)

Because movement of the c spine is also quite dependent on movement of the thoracic spine, we must also looks at Louise’s current set up:

- Thoracic spine stuck flexed= C spine stuck extended= skull stuck posteior tilt= larynx stuck in posterior tilt and descended (as in the lovely picture on the right I drew, above)

This could potentially be impacting her range and comfort into higher notes, but also into lower notes, as her larynx could be hanging out in a descended position all the time with nowhere lower to go (and indeed, she admits lower notes are tough for her to hit).

Because Louise attempts to extend her T spine by squeezing together her scaps, the more she sings with this as a postural strategy, the more she may experience shoulder and neck tension as she attempts to create a more elevated, anterior tilted larynx position for higher notes by tensing her shoulder blades, with an extended C spine.

Yet another interesting piece of Louise’s puzzle is her high arched, stiff, inverted feet. In the foot map of the body, developed by Gary Ward and Chris Sritharan of Anatomy in Motion, the metatarsal rays (1-5) are seen to be correlated in structure to the ribcage and thoracic spine. In Louise’s case, they share the same shape: Flexed (rounded) T spine with arched (rounded) feet- Both stuck in primary curves. As we attempt to teach her feet how to pronate, or, “extend” through the arch, it will be curious to observe what this could free up in her thoracic spine and ribcage into extension and impact on her breathing and neck alignment.

Louise and I discussed how a diaphragmatic breathing pattern can help to mobilize the spine: An inhalation will slightly extend the lumbar and thoracic spine, exhalation flexes them. Could her belly breathing pattern be the main contributing factor to her stiff spine via never quite mobilizing her T spine? Or, could her stiff spine the be major contributor to her belly breathing pattern? I suppose it will be both until we know for sure.

LET’S GET VAGAL

Of course I’m going to bring up the polyvagal theory. Because I think too much.

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is intimately related to the processes of breathing, vocalizing, and the striated facial muscles, making singing what Dr. Steven Porges may consider a “neural exercise”: One that combines the various functions of the vagus and serving as a portal for ventral vagal stimulation, and easier, quicker access to parasympathetic state of health, growth, restoration, and positive social engagement. Porges has described that both singing and playing wind instruments are ideal examples of neural exercise to “tone the vagus”.

Having just finished reading The Polyvagal Theory prior to working with Louise, I was curious about how singing could be used as a method of neuroregulation (which is one reason why I also wanted to study it). However, I was also curious how could this be affected by some of the inefficient habits I’ve observed in some singers, like poor breathing patterns, hyperinflation, over-breathing, spinal immobility, and poor internal pressure regulation, all of which in themselves can be correlated to a state of inhibition of the ventral vagal brake as stressors on the system, increasing sympathetic, fight or flight activity.

For example, a state of chronic hyperventilation (breathing in excess of metabolic demands, which can easily happen with the amount of mouth breathing involved in singing) could contribute to inhibition of the ventral vagus and increase sympathetic activity. Too, a state of chronic hyperinflation (common for singers who hold onto their reserve and never practice complete exhalations) is related to sympathetic activity due to the resting inhalatory (contracted) state of the diaphragm and exacerbated by the correlated extended position of the spine and ribcage.

In order for singing to be a portal for increased ventral vagal activity, do the mechanics of breathing need to be “optimal”? I’m sure they don’t need to be perfect, but for how long can one sing with inefficient mechanics until there is a negative effect? What is the sweet spot?

In other words, is the vagal stimulation via the act of singing- coordination of the various structures innervated by the ventral vagal branch, a sufficient counterbalance for these “non-ideal” breathing and postural habits (as we’ve been discussing in Louise’s case)? Or could enhancing the body’s fundamental mechanics, helping to make singing and breathing make singing less of a strain to the system, transform singing into an even more nourishing experience? And, much like an athlete stuck in a pattern of training that could be leading them to injury, does the act of singing in itself serve as an escape from noticing the poor habits associated with it until it is too late?

For me, dance was an escape from “reality”, and I imagine singing could be an escape for some individuals. Though I was a good dancer, I had shit for fundamental movement mechanics. Though I felt “good” while I was dancing- the escape into the flow state of the music, the movement, and my body, I was using this feeling an escape, and I ignored the symptoms of this (everything hurting). Eventually, ignoring the symptoms that dance was no longer nourishing me began to hurt enough that the escape was no longer even a possibility.

Could singing be similar? Do singers burn out the bodies in the same way that dancers and athletes do? Curious…

I’m probably just thinking too much. But if I don’t write down my thoughts here, they will fester and rot in my brain.

CONCLUSIONS?

It is lovely to reflect on the interdependent nature of all structures of the body like this. Lovely to attempt to map it with the Flow Motion Model (FMM). I am still questioning a lot of what I just wrote, especially the stuff about the larynx movement. If you know things that I don’t, I want to hear them.

Louise is an incredible singer already, but she has been noticing an increase in “support” while singing since working together. She also has had the realization that maybe she doesn’t need to take as big of breaths as she does, doesn’t need to hold onto as much air as she does, and can sing just as well, if not better, with healthier breathing habits. Apparently, what she’s been working on with me has also been useful for some of her students, too.

Very cool stuff. I’m interested to see how things go for her, both with singing, and her movement/strength training practice.

Louise is also my vocal coach, and I’m sure I will be pestering her to go into agonizing detail about the use of breath and larynx while trying not to embarrass myself singing.

Apparently, I have now agreed to be the terrible singer in a terrible ukelele and brass band. My only condition was that I get to keep the beat on a triangle, and that we perform only Wonderwall. Watch out, Toronto.