I had faith that strength training would cure my pain.

What do you think? What role does strength training play in healing from injuries and chronic pain?

I don’t necessarily have answers, but I have some humble thoughts.

When I first started working (customer service) at a gym in my early 20s I heard all kinds of things from trainers like:

“Your core is weak, that’s why your back hurts.”

“Your butt is weak, that’s why your hips are tight.”

“Your knees hurt because they are too unstable.”

Naive and impressionable, riddled with acute injuries and chronic symptoms from my dance training, I translated this to “I am in pain because I am weak, therefore getting strong and stable will fix my body”.

Long story short, I was wrong (and I will elaborate on the long story in this blog post).

The strength-healing fallacy

I think there is a logical fallacy here we can observe:

Training to become stronger will not necessarily result in healing, but physical strength is inevitably a by-product of a healing process.

I have an acquaintance that lives this fallacy out perfectly, to whom I will give the gender ambiguous name, Frankie.

Frankie thinks their 20+ years of chronic back pain is related to being weak. Because their back is in pain, they can’t workout to build muscle and strength like they used to. However, Frankie also thinks that a direct cause of their back pain is because of not working out and losing muscles and strength- Two panaceas for pain.

Frankie fears that losing strength and muscles will make their pain worse, therefore going to the gym to workout is the solution. Then Frankie is astonished when it doesn’t make things feel better. Worse, in fact.

I’ve done this, too! Been there, done that. How about you?

What if strength and health have an asymmetrical relationship? One supports the other, but the other doesn’t necessarily support it back.

The actual definition of strength: The capacity of an object or substance to withstand great force or pressure.

Think of strength as a quality or a state of potential one can develop when one is already in a state of well-being, not necessarily an act that will produce wellness.

Frankie was convinced that strength would produce healing and health, instead of seeing that first becoming well would allow him to restore his strength.

Now, what is healing?

“Healthy” is a BIG word and I think the definition is a little different for each of us. I won’t even try to tackle it right now.

The old English root of the word “heal” is actually “whole”.

My sense is that healing and well-being have more to do with the state of our system moving towards “wholeness” and integration, not as simple as being strong or weak.

Having access to our whole body must precede trying to strengthen it. Bodybuliders know this- You can’t stregnthen something you don’t have a neural connection with. The first 6 weeks of a strength training program is more about strengthening neurological pathways to our muscles than actually building them up in size and contractile ability.

We cannot strengthen what we cannot access.

So the 64000$ questions is: What has caused us to lose access to our bodies?

Injuies. Accidents. Periods of chronic pain. Learned movement skills, deeply ingrained. Habitual ways of moving (or not moving). That weird ear infection after which nothing felt the same again…

Could real healing be a process of reclaiming access to the individual parts we ignored, neglected, or never rescued from harm? And then a process of integrating them into context with each other, to work together as a whole?

And then in a whole, more structurally balanced state, there will be less pressure and strain from our bodies getting pulled asymmetrically to one side. Muscles that were stuck short get permission to lengthen, and visa versa. Joint spaces that were closed can begin to open and allow blood flow where previously it was impeded. The narrow pathways through which nerves must travel can deliver their signals can do so with less structural roadblocks.

So is access and integration are important for healing, how do we do this, if not by strengthening things?

What’s in a healing process?

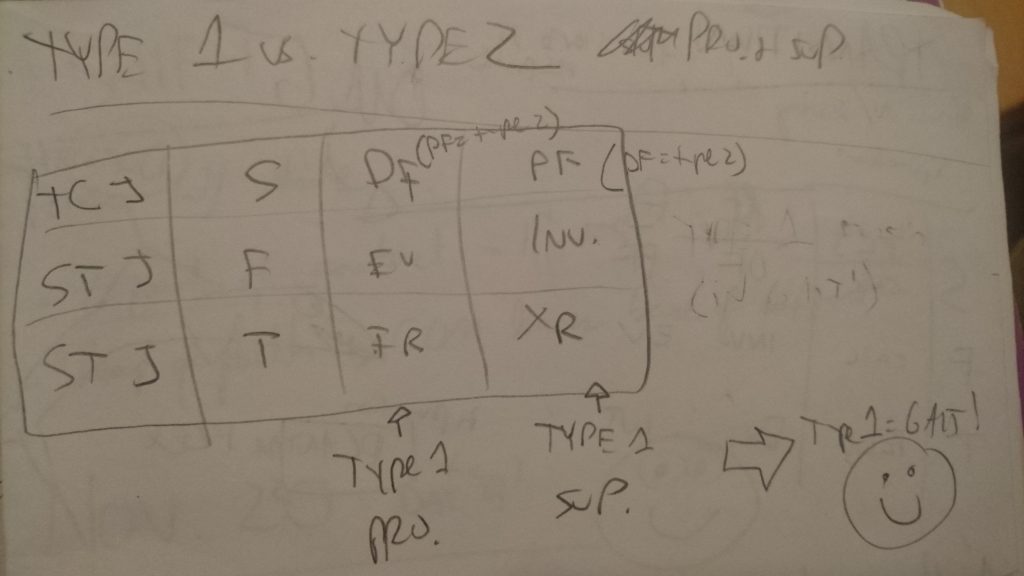

Here’s a chart I found on Symmetry Physical Therapy’s website:

It takes a real duration, weeks to months, for tissues to repair from mechanical damage, but that doesn’t imply completion of a whole process (involving the whole body).

Time elapsed doesn’t mean anything happened in the space of that time. It’s like a teacher saying, “you’ll need to study for 5 hours for this exam”, so you stare at the textbook for 5 hours thinking you’re engaged in the right action required for learning.

Are you engaged in the right action required for healing?

If I’m being honest, I’m still engaged in a process of healing my left hamstring. The injury happened 10 years ago. I’m quite sure I’ll be worthing with it for another 10 years, at least. There are so many factors impacting on this… Stories for another time 😉

After tissue repair, access to that body part needs to be reclaimed and integrated with the whole body again, as close to original instructions as possible. If we don’t attempt to do so, our body learns to move with a “dis-integrated” body part, disconnected. Mechanically attached, but not truly belonging to us like it used to.

And then we (and I am referring to myself) decide to lift some heavy-ass weights… Can you see a problem?

So could the real question be…

What’s preventing our bodies from healing?

Could it be… Us?

Could we be blocking our own capacity to heal by imposing a greater stress -strength training, upon it before we are ready, because of some idea we have- like the one I picked up at the gym about strength, but convinced we are making our system more resilient?

Could the effort of strength training actually be an output blocking our bodies’ innate healing processes? And why are we doing that?

Personally, the aggressive manner in which I attended to getting stronger (more on that story below) only served to reinforce the wonky mechanics and false beliefs that were keeping me stuck with pain. Yeah, the number of pounds I could lift showed I was objectively pretty dang strong… However, I was not very healthy, and still in a lot of pain.

So, what do we make of this? Theorizing aside for now, I’d like to offer my story and lived experience, for whatever it is worth…

Getting strong felt really great (until it felt worse)

I remember the exact moment I realized I was stronger.

I was 21 ish. One day I bent down to get something from the bottom shelf of my fridge (probably a tub of I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter, because I was addicted to that stuff. I’d mix it with pure white sugar and eat it with a spoon…), and when I stood up, I actually felt some oomph in my legs I’d never noticed before.

Whoah. What the… Am I getting stronger? This feels amazing! What if… Maybe… Could it be… that how I feel in my body is more important than how it looks??

“Strong” was a weird, new sensation for a person intent on making herself smaller, who had formerly, distortedly, associated weakness with success (that’s what a calorie deficit feels like- Profound, inner weakness).

This feeling of power in my body was an important reminder: That perhpas reclaiming my personal power was more important than fitting an unreasonable physical standard- What a body should look like.

But I ruined this beautiful insight by rationalizing that getting stronger could be the new correction of everything I believed was wrong with Me.

And if weakness is the problem, and being strong feels good, then logically absolute strength is the solution.

What’s the most linnear path to absolute strength? Powerlifting. Anyone who can lift 225lbs off the floor can’t possibly be in pain. Right??

Hmmm… Not really.

Did getting strong help with my pain? Yes… For a while, but only because I forgot my pain was there.

And then… things started to crumble.

My lower back pain began to flare up after back squats. Pushups would exacerbate my back and shoulder pain. Something as seemingly innocuous as a single leg deadlift, without any weight, produced deep, grindy pain in my right hip and SI joint.

Gradually, I was left with a smaller and smaller pool of exercises that I could actually do pain-free (sort of):

Hip bridges and planks felt OK (and by “OK” I mean didn’t make things worse).

My upper body could only tolerate rows and horizontal pulling (but to be honest, still hurt my shoulders, just not in an existentially threatening way. And the internet said “rows are good for shoulder health”, so I kept at it).

But despite all actual evidence otherwise, I still had faith that strength would set me free. Why?

Strength: An amazing tool to ignore life’s problems

I remember a meditation teacher once said to our class that being busy with something unimportant that feels productive is a form of laziness. Laziness not being limited to simply sitting on one’s butt, but using something as a distraction from what is actually important.

Paradoxically, my laziness manifested as strength training, and it was an amazing way to distract me from facing some of the uncomfortable facts about how I was living my life.

Here’s a few ways I learned that strength training can be used to ignore my body’s (and life’s) problems:

First, when strength is a novel stimuli, it will take center stage.

It’s how our nervous systems are wired. The new physical strength I was building, manifesting as the pleasant body-feeling of power, was so novel as a sensory experience that I was able to push all my noisy joint (and life) pain into the wings.

Too, the novel and productive pain of DOMS (delayed onset muscle soreness) was a sensation that distracted me from the more subtle, nauseating feeling in my solar plexus. You know, that visceral senes that something’s wrong, but you can ignore it if you keep busy enough?

If my body was tightly gripped in a neuromuscular stress reaction 24 hours a day, I couldn’t tell, because my muscles were constantly sore from working out and I felt powerful. It felt useful.

The pain of building strength was a pain I chose to endure. A pain I can put myself through is preferable to a pain I cannot control, like the pain I had in my spine, hips, and SI joint, to which I felt like a helpless victim.

I’d willingly suffer the micro-trauma to my muscles, rep after rep, knowing that the by-product would be a pleasant, empowering body feeling that could temporarily numb the pain in my joints.

During the grueling, physical exertion itself, endorphins- our natural pain-soothing peptides, circulating into my bloodstream, helped me to numb out the unpleasant feelings in my body.

Strength- building it and languishing in its nice-feeling by-products, was a good diversion from my pain signals. The consequence, however, is that I became disconnected from the afferent signals my body was sending up to my brain about the actual state of affairs: “Monika, you’re just a few steps from self-destruction…”

Second, it felt very productive to occupy myself with learning about how to get strong.

Having let go of my identity as a “dancer”, I craved to replace it with something else. I chose “lifter”. This meant filling my mind with as much information as possible on the subject so I could talk the walk.

Reinforcing an identity feels very productive, doesn’t it? And feeling productive, I discovered, was another great way to ignore that awful feeling in my gut that I was on the wrong path.

So I immersed myself in a pth of intellectual conquest. I read the fitness “literature”. I took courses. I spent countless hours on Youtube becoming indoctrinated with not only WHAT exercises to do, but WHY being strong would make me a better person.

A strong butt, in particular, was directly correlated with a higher moral state. The video below is a good example of this. Why YOU NEED strong glutes:

Beware oversimplifications like this, which cam, ironically, come accross as incredibly complicated. Glutes are no more or less important than any other muscle, unless we place that importance upon them.

Third, through powerlifting I found a sense of acceptance from gym people.

I loved having a supportive crew of powerlifting pals, but if I’m being honest, my lifting crew was enabling me further to use training as an escape from my life.

The trap was that it felt so positive and inspiring. We were each others’ cheerleaders. “Add 5 lbs more!”, “You can do one more rep!”. It all felt very uplifting. But it wasn’t helping me face my facts.

The fact was, unbeknownst to these people I considered my friends, they weren’t actually interacting with Me, they were talking to a sleepwalking representation of who I wanted you to see.

They were talking to a robot with a body moulded to look and perform like a lifter. The conversational content limited to information I’d accumulated about lifting. And by that representation alone I thought friendship could be forged.

The fact is, underneath the image of heavy-ass-weight-lifting person, I had no real social skills- I’d been avoiding developing them by building up this “acceptable” appearance that could compensate for it. And I had no idea.

They could not have known that underneath the persona of lifter, there was nothing even there to interact with. Try to have a conversation with Me, not the lifter, and I would have had nothing to say.

If I look like someone you’d like, isn’t that the same as Being someone you’d like? I don’t have to work at being a friend if I can just look like a person you’d want to be friends with.

They could not have known my hidden motives. It is even possible they were doing it, too.

And lastly, to actually become strong requires discipline, control, and manipulation, which can be addictive

Control and structure feel very productive.

In my addiction to control, I poured all my energy into manipulating every facet of my life that would support my identity of power-lifter, and telling everyone about it:

- Keeping a strict training schedule

- A strict, “healthy” nutritional plan (aka orthorexia in disguise)

- Fine tuned sleep schedule

- Avoiding social events that would expose me to “bad” food

- Taking supplements

- Reading, learning, studying all things to do with strength development.

Sounds all good and healthy, right? Not if you knew it was all a compensation to avoid honestly looking at Me. And the consequences were that I became numb in a new way. Isolated. Out of touch with reality.

The consequence was that I became completely disconnected from my body’s natural state of well-being. I wasn’t healing. I was forcing myself into a persona that wasn’t Me, thinking it would fix me. Becoming more and more split. More numb to my pain.

And in a numbed-out state, any action that feeds an identity is likely to only reinforce becoming more and more numb through that identity.

Today, I’d rather feel my pain and face my facts than be “strong” and numb. But that’s a state that took a long time to accept. And is still a work in progress that takes daily committment.

I’ll end the story here for today. There is more to share another time.

Can you relate?

Have you ever used a movement practice or form of exercise as a distraction from pain, and misinterpreted that distraction as a solution for it?

Have you ever used a solution for your body’s pain as a fix for your life’s problems?

Working for a physical quality: Strength, flexibility, even becoming more “relaxed” using meditation and breathing techniques, can be an escape. A means to feel in control. A way to numb out from the body sensations that are communicating to us that something’s not right.

For example, what if one says “I need to exercise for my mental health!” This may be true…

But perhaps more clarity could come from asking, “What is causing my mental health to suffer and I feel the need to use exercise to correct?” i.e. compensate for.

(Which is not to say that there isn’t evidence supporting exercises’ role in brain health- The book Spark by John Ratey is an excellent book about just that- Just that we ought to be clear on our intentions and honest with ourselves about it).

But we ought to question, is exercise the escape from seeing the root of the problem? The attempt to correct a problem that originally had nothing to do with exercise? A problem that has ntohing to do with being strong or weak or fit in any way? And if you attended to that, would you still feel the need to exercise?

And how does one become grounded in the actual experience of our bodies, without using exercise as a way of pretending to have already attained to that?

These questions, among others, are ones I think I might explore for the rest of my life.

I have more to write on this topic, but that’s another post, for another day. I’d love to hear your thoughts and answers to the above questions, if you’re open to creating this space for honest discussion around our relationships with exercise, and our bodies.

Please leave a comment below! Or shoot me an email! Or follow me on the IG (@monvolkmar), if you’d like to keep this conversation rolling 🙂