Alternative title: Foot pronation is not the devil.

If you don’t want to read this whole blog post (won’t take it personally, my posts can be long…) go to the bottom to watch an excerpt from an online movement session I did last week linking foot and jaw mechanics in gait.

Go with the flow (motion model)

About once a week I do a movement session with students who’ve completed my Liberated Body 4 day workshop. The intention is to help them deepen their understanding of how our bodies were designed to move based on the joint interactions taught in Gary Ward’s Anatomy in Motion, and his Flow Motion Model of the gait cycle.

I love this model (FMM) because it maps how any one part of the body is linked to all of others via their joint interactions through the gait cycle.

We can use the model as a map to identify the joint motions and interactions your body is having truoble accessing so we can give these sepcific things back to your system.

Peoples’ bodies tend to like feeling more complete.

I thought it would be nice to summarize one of my most recent online movement sessions in which we looked at the joint interactions that link movement of the foot with the jaw.

The very short story: Foot pronation couples with jaw decompression (mandible sliding forward and down from the temporal bones).

My invitation to you, if yo’re interested, is to come take this journey from your foot to your face. It’s fun. It’s logical. It will hopefully even be useful! (and check out the video at the end of this post to see a clip from the session to follow along with).

WHAT IS THE JAW?

Seems like an obvious question. However, I’ve made it my personal practice to never again take for granted that I understand what a joint is. Nor will I assume that the person I am talking to has the same understanding of a joint as mine.

I fondly recall the moment I actually understood what a shoulder was. It was just last year…

So when we say “jaw”, what’s the reference point? Are we talking about the mandible? The temporal mandibular joint (TMJ)? Where does the word jaw even come from?

I did a bit of etymological research and tfound that “jaw”, from mid 15th century old English referred to “holding and gripping part of an appliance”.

Holding and gripping… Sounds like what many of us do with our jaws today.

Your jaw is actually the “gripping” part of your face. Feels true, don’t it? 😉

The jaw has two articulating bones: Mandible + temporal bone.

In desribing the motion of the jaw, we’ll refer to the mandible’s movement interaction with the temporal bone.And we’ll consider the temporal mandibular joint- TMJ- as simply the space between the mandible and temporal bone. There’s a articular condyle in there. And some synovial fluid, too.

We’ll use the words protrusion (forward) and retrusion (backwards) to refer to mandibular motion in relation to the rest of the skull. And we’ll use the words compression and decompression to refer to the TMJ’s state of more or less pressure respectively.

As you open your mouth the mandible protrudes (slides anteriorally and inferiorally) opening space in the TMJ, and we’ll call it a decompression. And visa versa.

For purposes of this blog post, we’ll talk mostly sagittal plane (forward and back movement), but know that the mandible and TMJ have movement capacity in frontal and transverse plane- lateral shifts and rotations right and left. Not a lot, but enough to be significant.

Now the fun part… Your jaw has a specific way of interacting wiht the rest of the body as you walk.

All joint motions the body can do show up in gait. Even the jaw’s motions, though it is so subtle and happens too quickly to pay attention to it unelss you really focus.

Every single joint in the body has the opportunity to articulate to both ends of it’s available movement spectrum, in all three planes, with each foot step. Every movment your body can do it does in the space of 0.6-0.8 seconds with each step.

Unless it can’t.

So if a joint doesn’t have access to a movement just standing and trying to isolate it, you can bet it won’t be happening when you walk either. This leads to new strategies that are more effortful, and may lead to new problems later.

How does lack of movement at the foot affect the jaw? How does lack of movement at the jaw affect the foot?

The jaw is a DANGLER

In AiM, Gary has taught us to think of several structures as “danglers”.

The mandible is a dangler.

Because it dangles, it doesn’t really do much on its own accord as we walk, it just comes along for the ride. It doesn’t actually have inherent motion that contributes to gait, but think of it as needing to sway in harmony with its surrounding structures as part of a global mass-management strategy.

When the jaw gets stuck in one position and only has that one option, it can impact on the movement options for the rest of the body.

OCCLUSION, PROPRIOCEPTION, AND THE RETICULAR ACTIVATION SYSTEM

Occlusion refers to where the surfaces of the teeth touch. This can have an impact on whole body on movement potential.

In my early AiM days, I recall that I couldn’t find my hamstring load in the heel strike (hamstring “stretch”) exercise on my left leg.

Then I randomly came accross a chart with the teeth and their association to different muscles. I’ve misplaced said chart and all I remember was the connection between molars and hamstring (and if anyone has this or a similar chart I would love to see it!).

Just for the fun of it, I tried doing the heel strike exercise while holding contact with my left molars. BOOM hello hamstrings. Freaky biomechanical magic.

(If you want to learn more about heel strike and how the hamstrings load in gait, I recommend Gary Ward’s Lower Limb Biomechanics course. So good!)

It is also said that the jaw is said to contain the highest number of proprioceptors compared to any other area of the body. Meaning we get a ton of information about our body’s orietation in space from our jaw. And because we can’t see our own jaw, we probably oreint our body’s center of mass based on our jaw’s perceived center to some degree. (I am going to make a little video soon for you to play with this concept… stay tuned!).

Lastly, its good to know that the muscles of the jaw are supplied by the trigeminal nerve, which is closely related to the reticular activation system, which helps us filter information from our environment into categories of safe vs. unsafe, and is linked to states of anxiety, stress, anger, etc.

A curious personal observation is that on days when my bite is more centered, I’m usually in a brighter, cheery mood, full of optimism, and my body has less of my usual annoying symptoms. When my bite is off (usually shfited, laterally flexed, and rotated left), I’m likely to be more irrtable and triggerable by silly bullshit, and more of my symptoms may be present. N=1, but its been useful to pay attention to this.

All this to say, TMJ mechanics and resting bite can have an effect on how we move and how we feel. So we want it to be able to dangle freely, in the right relationship with the rest of the body, which should happen in a particular way with each step we take.

“DEMONIZED” MOVEMENTS THAT COUPLE WITH JAW DECOMPRESSION

What happens when we start labelling one movement “good” and another bad”? We avoid the bad ones and do more of the good ones. This may be conscious or unconscious.

Either way, avoidance of a movement is problematic because no joint motion in the body happens in isolation, but in relationship with everything else.

In gait, if one joint moves, every joint moves.

So when I ask your foot to pronate, I’m actually asking your whole body to pronate with it- A foot pronation accompanied by all the other joint motions that should happen at the same snapshot in time at which the foot pronates in gait.

Have you been taught that pronating your feet was bad? I was. Like, hardcore by my ballet teachers. To the point that I thought that I was a bad person for pronating my feet. (we were also made to feel bad about having to go take a pee in the middle of class, so I held my bladder a lot back in tose days… I think I wrote about that in my book Dance Stronger)

Here’s the paradox: Can a movement deemed “bad” happen at the same time as another movement that is “good”? And if yes, then does this make the good movement more bad? Or the bad movement more good?

Neither. They both just happen. No need to place any meaning or judgement.

To give you an idea of the stuff we recognize as “good” that happens when the foot pronates:

- Glutes load (leading to a glute contraction that then extends the hip)

- Big toe decompresses

- Occipital atlantal joint (neck-skull joint) decompresses

- Plantar fascia and all muscles under the foot load and stretch and then help your foot supinate

- Vastus medialis gets to do something useful (decelerate knee flexion)

- TMJ decompression (as we are focusing on today!)

And more.

On the flip side, there are many other joint mechanics that couple with foot pronation are generally deemed “bad” for the body. A few of such terrible movements are:

- Pelvis anterior tilt

- Knee valgus

- Spine extension

- Hip internal rotation (although perhaps only in the dance world… we love to hate on hip internal rotation)

But remember, please, none of these movements are inherently bad or good. They simply happen.

What makes a movement better or worse for us is if it is happening too much, too fast, at the wrong time, or we get stuck in it as our only option.

Pronation is a like visiting Walmart. You want to get in, get what you need, and get out.

When we lable a movement (or anything…) as bad its often because we don’t understand it in its proper context, so our solution is to try to minimize, avoid, or control it.

Real freedom isn’t reached by controlling and manipulating our bodies, selectively avoiding entire movement spectrums. Just a little perceptual recalibration is required.

Let’s follow the flow (Motion Model)

In theory, using the Flow Motion Model, one can look at any bone or joint and, based on its position and velocity on the space-time continuum (if one can really measure both simultaneously…), one could extrapolate what the rest of the body should also be doing at that time moment in time. I think that’s pretty cool. Useful, too.

This is how we are able to make the connection we’re interested in today: Foot pronation couples with TMJ decompression.

If you’re up for it, join me now for a delightfully logical adventure through the body, joint by joint, from your foot to your face, linking foot mechanics to jaw mechanics.

I hope to highlight how movements like pronation and pelvis anterior tilt, which somtimes get a bad rep, are coupled movements. “Coupled” meaning that we want to see them happening at the same moment in time in gait.

Heel strike and away we go…

Let’s start at the beginning…

… with the moment your heel hits the ground, and follow your foot as it rolls into it’s most nicest, flattest position.

For simplicity, we’ll call this moment in time pronation, and we’ll defnine it as the one chance your foot gets to pronate on the ground in gait. Its the moment in time at which many mechanics of shock absorption spring into action (get it??).

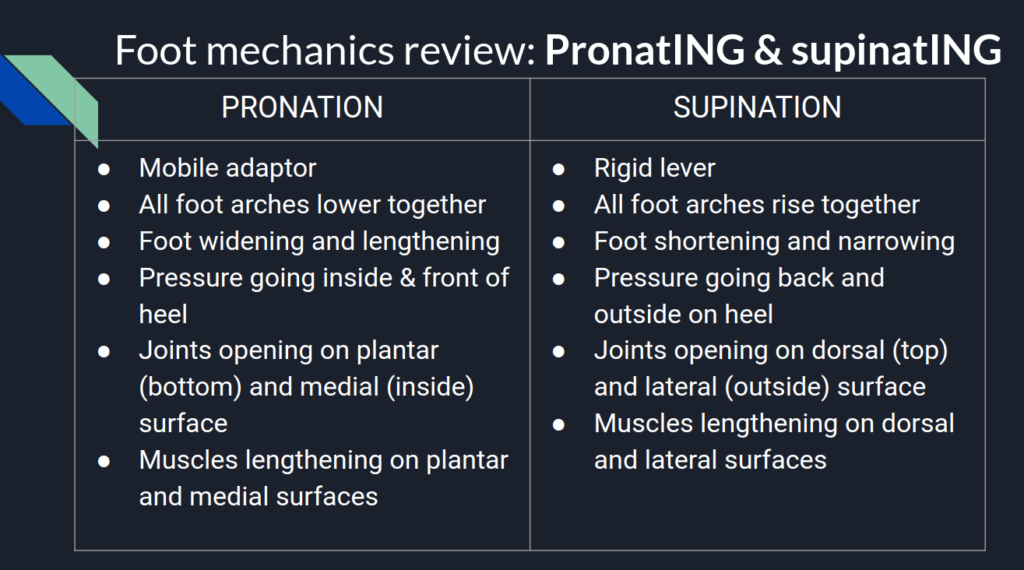

Let’s keep things super simple and define our pronating foot in terms of pressure, shape, open vs. closed joints, and long vs. short muscles.

As your foot fully pronates in a healthy way, and hoping it can maintain three points of contact- on the 1st and 5th metatarsals and your heel- you should notice the following:

- Pressure on the foot travelling anterior and medial towards the 1st metatarsal joint.

- All foot arches lowering and spreading, foot shape is becoming wider and longer.

- All joints opening on the plantar/medial foot, and closing on the dorsal/lateral surface.

- Muscles lenghtening on the plantar/medial surface, and shortening on the dorsal lateral.

And all the reverse mechanics happen as the foot supinates.

Pronation of the foot should happen with knee flexion. Let’s check if that joint interaction is naturally present for you.

What’s happening at your knees? If you stand on your two feet and bend your knees, without trying to do what you envision the perfect version of a knee bend should be, do feel your feet naturally pronate, as described above? How do your feet naturally respond? Has your training, like mine, been to avoid pronating your feet? And whait happens if you suspend that belief about pronation being wrong?

If you had no prior information about what SHOULD happen what do you feel IS happening?

If your foot pressures are going the opposite way- lateral and posterior towards your heels, what does it feel like to allow the pronation to occur?

Yes, your knees may go slightly inward. A little bit is ok. A lot is not. Embrace your right to valgus in this moment. The real money is when you don’t need to use a knee valgus to pronate your feet.

What’s your pelvis doing? As you bend your knees and pronate your feet, are you doing a pelvis anterior or posterior tilt? We’d like to see an anterior pelvis tilt. Why?

Feel this out: As you anterior tilt your pelvis, notice how this internally rotates your femurs, tibias, talus(es), and all that internal rotation should contribute to both feet pronating (talus IR is part of foot pronation).

If you do a posterior tilt with your pelvis, you drive supination mechanics via an external rotation of all those leg joints. Maybe posterior tilting is a good way to avoid pronation. But also, maybe you don’t need to avoid pronation?

Also note there are two ways to anterior tilt the pelvis, and only one of them is useful in gait (watch the video below…)

What’s your lumbar spine doing? As you anterior tilt your pelvis, what is the natural, uncsonsioud response at your lumbar spine? We know that as the sacrum nutates with the whole pelvis anteriorally tilting, the lumbar spine will follow into extension. But what does YOURS actually do? Also consider, does it feel like you use your lumbar extension to anteriorally tilt your pelvis? Or does your pelvis anterior tilt lead to a nice extension of your lumbar spine?

What’s your thoracic spine and ribcage doing? As your lumbars extend, does that extension continue to flow up into your thoracic spine, tilting your ribcage up and back (posterior tilt)? Should do! Unless you have a restriction blocking that spine wave up.

What’s your cervical spine and skull doing? Keep your eyes on the horizon, stand on your happily pronating feet, and notice, with spine extension, what motion do you feel happening in your neck? Does your chin lift up and extend your neck? Or do you feel your chin drop and your neck flexing?

Hopefully you feel your kkull anteriorally tilting and your neck flexing. Occipital atlantal joint decompressing.

And finally…

What’s your jaw doing? Remembering that your mandible is a dangler, let it dangle as you tilt your entire skull anteriorally, with your spine extending underneath. Which way does your mandible slide? Forward and down (protrusion/decompression from temporal bone) and dangling further from your face? Does it retract back in towards your face? Or does it do nothing?

Ideally, what you’d like to feel is the jaw sliding forward. Decompressing. If you try to keep it retracted it will seriously block your ability to flex your cervical spine. Just try it!

This is the flow:

Foot pronation –> Knee flexion –> Pelvis anterior tilt –> Lumbar and thoracic spine extension –> Neck flexion –> Skull anterior tilt –> Jaw protrusion/decompression

Do you have all these links in the chain? Or are there some blocked interactions?

If that was too wordy, I invite you to follow this adventure guided by me! Here’s a clip from the session last week in which we did this exploration.

How’d that go for you? Got all the links in the chain? Would love to hear what yo uobserved.

And if that wasn’t so smooth and flowy for you, what do you do about it? Perhaps you’d enjoy my workshop, Liberated Body. which I am now teaching online via the ubiquitous Zoom. Liberated Body is all about finding the missing links in your own body, and restoring them to have a richer experience of your body.

The next workshop is coming up in a few weeks on June 27th. Tell yo’ friends.

Until next time, my fellow body mechanics detectives 🙂