A few weeks ago I went on a canoe trip with my dad to the beautiful Kawartha Highlands Provincial Park.

On the 2.5-hour drive, my dad told a story about “that time I had car trouble and blah, blah, blah…” (you know the kind your parents tell that you smile and nod through, but aren’t actually interested in?).

To my delight, his story contained an unwittingly wonderful insight from a Toyota dealership mechanic explaining why we get injured, and a simple heuristic for how not to.

Turns out listening to what your folks say is useful sometimes.

To get started, we need a basic primer on how the brakes work in hybrid/electric cars (trust me, this is going somewhere…).

The Problem With Regenerative Braking

My dad has a hybrid-electric car. A Toyota Corolla, to be specific.

Hybrid vehicles are built with mechanisms that make you morally superior save you fuel and battery life beyond all those other gas-guzzling, Earth-poisoning, death-mobiles.

One such mechanism is called regenerative braking.

What is regenerative braking?

Unlike conventional friction braking systems, which work by physically clamping the wheels to stop them from turning, regenerative brakes work by running the wheels “in reverse” to slow the car down. Simply taking your foot off the gas pedal initiates the regenerative braking mechanism. Additionally, the resistance created by the motor charges the battery. Cool, right? I thought so!

But here’s the important part: This mechanism causes the car to slow down a lot faster than a non-hybrid/electric, and so you don’t need to step as hard or as frequently on the brakes.

Just a little tap, taparoo.

Apparently some regenerative braking systems as so highly sensitive that just taking your foot off the gas pedal is enough to trigger the brake lights.

Sounds like a win-win-win, right? Saves your brakes the wear and tear, preserves the battery life, and gives you more miles per gallon.

But… And this is an important but. There is an ironic darkside.

A lot of hybrid and electric car owners (such as my pop) find that their brakes are actully wearing out in spite of using them LESS. What the heck?

This is when my ears perked up in my dad’s boring car story. Wait, what? Why would brakes wear out if the system is set up so that you use them less??

Use it or lose it

The “use it or lose it” principle is usually discussed in the context of the brain, neuroplasticity (the brain’s capactiy to re-wire neural circuits based on new inputs) and body- If you consistenly stop exposing a particular set of neural circuits or body parts to stimuli, your system interprets there is no need for them, and you “lose” access.

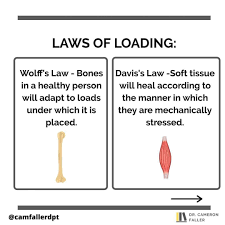

Or remember Wolff’s law. Bone remodels and lays down new cells based on the forces imposed upon it. This is why after a bone fracture force needs to go through, i.e. bear weight on it, it to stimulate new tissue development and heal.

This is also how bone spurs develop- Muscles pulling excessively on a bone will stimulate it to grow.

This is also part of why some folks get osteoporosis. Lack of weightbearing exercise with high enough forces to stimulate bone to grow. If you don’t use it, you lose it.

*NOTE: See a completely unrelated story about a 97-year-old-woman and her osteoporosis at the end of this post.

The remedy for use it or lose it is to start using it again (and this becomes harder and more daunting the longer you wait).

What does this have to do with brakes?

Apparently, the use it or lose it principle applies with regenerative braking. Because the system is set up for inherent disuse (ironically positioned as a key benefit), the brakes are prone to corrosion because they don’t get used often enough.

You’ve seen how a bike chain rusts and stiffens if you leave it out all winter. Use it or lose it.

If you don’t deliberately “exercise” the brakes frequently and forcefully enough, when the time comes you actually DO need to hit them hard, say, to avoid running over a kitten, those rusty rotors might fail under the new load.

As the mechanic at the Toyota dealership told my dad’:

“If you have a hybrid car, you won’t be using the brakes as hard. You don’t really use them as much as you would in a regular car. So what you kind of have to do once in a while is deliberately brake really hard to make sure they aren’t getting stagnant from disuse and accumulating corrosion”.

All I could think was, well isn’t that just how bodies work…

Bodies get “corroded” from disuse, too, and then wear out “suddenly” when exposed to a demand they weren’t adequately prepared for.

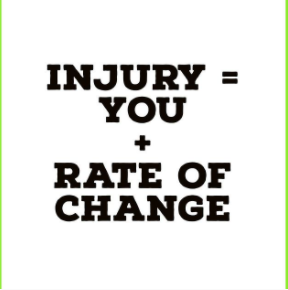

Or, as Gary Ward expresses the equation: Injury = You + Rate of change

Another example you might relate with…

Were you super excited to get back to working out after a year of lockdowns? Did you mayyybe go back to your prior routine full-force like no time had passed? But all year long you didn’t once “tap the brakes” to keep all your body parts moving? (as a bodyworker/trainer, I saw a lot of this in 2021…).

And how many other so-called “syndromes” and “diseases” might actually have roots in disuse? Some types of arthirits? “Frozen” shoulder? Ankylosing spondylitis? Is disease the reason for disuse? Or is disuse the cause of disease? How do we count our chickens and eggs??

I’m not a medical professional, just a lowly bodyworker, and what I observe is that many labels are nothing more than fancy ways of saying, “a thing that stopped moving and now hurts and we’re not sure why…”. (and I also recognize that many labels are genuinely useful and liberating).

So if the problem is that you just stopped moving it, maybe try… Moving it? Sensibly, of course (that’s where people like me come in to help ya).

And much like the regenerative brakes on your uber-efficient hybrid/electric car, nothing seemed wrong, until…

It just came out of nowhere!

It didn’t come out of nowhere. You just weren’t aware of how little that body part was actually moving prior to the issue.

Disuse is a perfect set up for corrosion, mechanical damage, and malfunction of the non-moving parts. For your body, and your brakes.

Ankle sprains are a good example. Lots of people have sprained at least one ankle.

If you spend most of your life never exposing your ankles to the demands of ankle-rolly bumpy terrain, the soft tissues supporting your ankles (muscles, tendons, ligaments) are just like your car’s disused brakes: Slowly “corroding” away from disuse, but you don’t even notice because it’s so gradual, and you never put yourself in situations in which you even need to know your ankles exist, let alone use them in a challenging situation.

And then, one fateful day, whilst out walking your beloved pooch, you randomly trip, roll over your ankle, sprain your deltoid ligament, and realize how cushy your life has been.

Did that injury really “just come out of nowhere?” Or were you setting yourself up for it for years because you didn’t ever deliberately use the structures that would have (should have) checked your ankle from rolling over and causing damage?

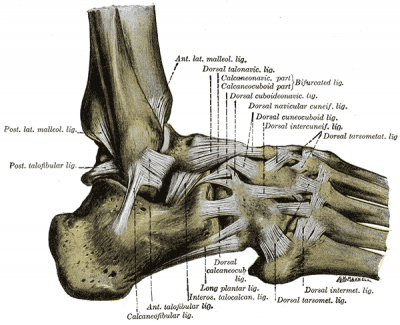

Look at all those amazing ligaments (ie “brakes) in your ankle and foot! Use ’em or lose ’em.

How many of our injuries that just came out of nowhere are the result of the “regenerative braking paradox”?

Joints act, muscles react

I am reminded of Gary Ward’s second big rule of motion: Joints act, muscles react.

And how are muscles reacting? To decelerate excessive joint motion away from center.

This is why his work centers around helping people discover the eccentric loading (the muscle contraction as it lengthens) of their muscles to manage (slow down) joint motion. This is akin to “tapping the brakes” at every joint in their body, to check excessive motion that could end up in an unsafe, potentially harmful range of motion. Like in our ankle sprain example.

If you can teach your body to move based on the joints act, muscles react thought process, then you are keeping your intrinsic regenerative braking system responsive, healthy, and on-point.

I encourage you to read more about this, and the other 5 big rules of motion in Gary’s book, What The Foot.

Conclusions?

I LOVE that what I anticipated would be another boring “that time the car broke down” story actually turned into an amazing analogy for how to keep our bodies resilient and healthy.

If you don’t deliberatedly use all the bits and pieces you are built of with enough frequency and force to keep them at peak function, you risk losing function of said bits and pieces. This has been my general movement practice philosophy for years, and I was tickled that it has a parallel in an area I know nothing about: Car brakes.

If you don’t use the brakes often enough to know if something’s not functioning well, you’ll never even know there’s potentially a problem.

Do you deliberately use your ankles often enough to know they can manage a roll?

Do you explore using your wrists often enough to know they can support you in a fall?

Do you purposefully flex your spine often enough to trust it can tolerate sneeze #55837? (apparently the average person sneezes ~70000 times in their life… Don’t ask me if that’s an accurate stat)

A car’s brakes manage it’s motion, just as our body’s soft tissues are like brakes that manage our skeletal motion. A movement practice based on “joints act, muscles react” trains the body to effectively decelerate potentially threatening wayward motion. This is NOT the same things as stretching and strengthening.

I am also reminded of how counterintuitive it can be to know how to care for ourselves…

Did the folks who built regenerative brakes intuit that they would create the disuse problem and lead to many cranky customers wondering why their brakes were shot even though they barely used them?

Did the folks who built the comfiest, thickest-soled, most ankle-supportive shoes ever intuit that it could cause a disuse problem and the plague of immobile ankles and feet? “But I never DO anything extreme to cause damage and I always wear my orthotics! Why are my ankles so shit?” (that’s exactly it, my dear…)

If only our bodies came with a user manual, and a well-informed, honest mechanic from the dealership…

Well, fortunately there are people in this world who are dedicated to helping you write your own body-owner’s manual.

People like me. And I am just one of many.

My aim is to empower people to learn about their bodies so they can rely less on therapists. And at the very least, be able to better communicate with them so they can get the collaborative care they need.

In fact, this is the most frequently reported benefit from my Liberated Body students: “I can communicate with my physio/massage therapist/chiropractor better now and it feels more like teamwork than blind faith”.

This is important, because advocating for our health is not easy when we don’t know anything about the thing needing fixing, leading us to naiively believe that we need to come back to the friendly chiropractor to get our neck adjusted every week for the rest of our lives… Don’t buy it.

If you’d like to learn more about how your body is built to move so you can systematically explore and prevent the disuse problem discussed in this blog post, I recommed checking out my online course Liberated Body.

Liberated Body is a series of four movement lessons based on the teachings of Gary Wards’ Anatomy in Motion. You’ll learn how your body is meant to move through the gait cycle (how you should be able to walk), and then compare whether or not YOUR body can access all those mechanics correctly.

Check out Liberated Body HERE. You can do it as a self-study, or look for the next live (online) workshop date.

Or whatever. Just make sure you keep tappin’ those brakes ahrd every once ina while to make sure they still exist.

*THE STORY:

If you have osteoporosis, can you improve your bone mass? Some people say that you can’t, you can only slow it’s wasting. I thought so, too. But then one of my clients told me a story about a 97 year old woman she knows with osteoporosis who made it her mission to build her bones back. Apparently she did exercises for 3 HOURS DAILY (I forget if it was for a year, or less), and when she went back to get her bone density tested again, it had gone up! I think only by a few percentage points. But how inspiring is that? And honestly, if you’re 97, you’ve definitely got the time and no excuses to commit 3 hours per day to rebuild your bones. And now the running joke when she says something can’t be done is, “Just put in 3 hours a day”. No excuses.