OMG Shoes.

One of the most frequently asked question I get from clients and random folks on the internet is, “What kind of shoes do you think are the best?”. (obviously the ones that are 300 f#@*!&g dollars).

First, you don’t want to wear the shoes that I think are the best, because you’re not me.

Second, “best” is going to be different for everyone.

Third, no one can tell you flat out what is “best” for you, in any area of life, but also with shoes. Getting guidance is good, blindly following shoe advice is bad, and having a system to learn how to choose for yourself is the best.

And I have to confess that at the time of writing this, I am experiencing pain in my right foot such that I have to wear squishy slippers to not be in agony. Me forcing myself to go barefoot around the house won’t “Strengthen” my foot and eliminate the pain. Its a little more nuanced than that.

But, this isn’t about me. This is about you becoming a person who can think better about shoe choices.

So, are you wondering about what to look for in a shoe? Are you wearing minimalist shoes when it might not be in your best interest? Are your shoes keeping you stuck in pain or moving inefficiently? Read on.

Are you looking to join a barefoot shoe cult to justify your beliefs? Wrong blog post.

Are Your Shoes Working For You?

Two summers ago, I did my first ever online Movement Nerd Hangout called Are Your Shoes Working For You?, in which I presented a simple system to test the impact different shoes can have on your individual movement options.

Assuming the universal goal is “I want my body to feel WONDERFUL”, there are definitely a few key things to keep in mind when selecting a shoe.

First, check out this snippet from the shoe hangout in which I discuss the 5 things I look for in a shoe (and the whole hangout session is almost 90 minutes of shoe/foot/body detectivery, if you have the time for that).

5 Things I Look For In A Shoe

In summary:

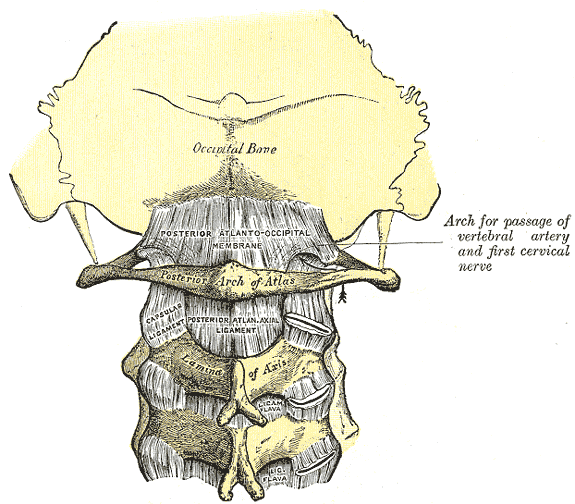

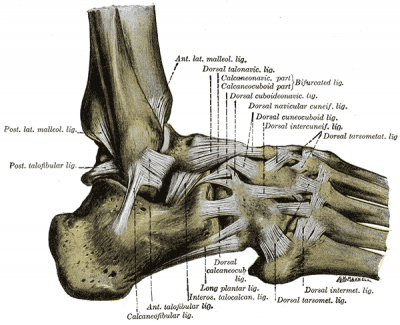

- Your feet need to be able to pronate and supinate in the shoes.

- Try to choose soles that are as thin/flexible as possible but as thick/supportive as necessary.

- Toe box should wide enough to accomdate the foot’s natural spreading in pronation,

- Your body mechanics should not be negatively impacted by your shoes (this is where the Does My Body Like My Shoes? system comes in handy)

- You must like how they look. Seriously. Live life in style 😉

The Does My Body Like My Shoes? System

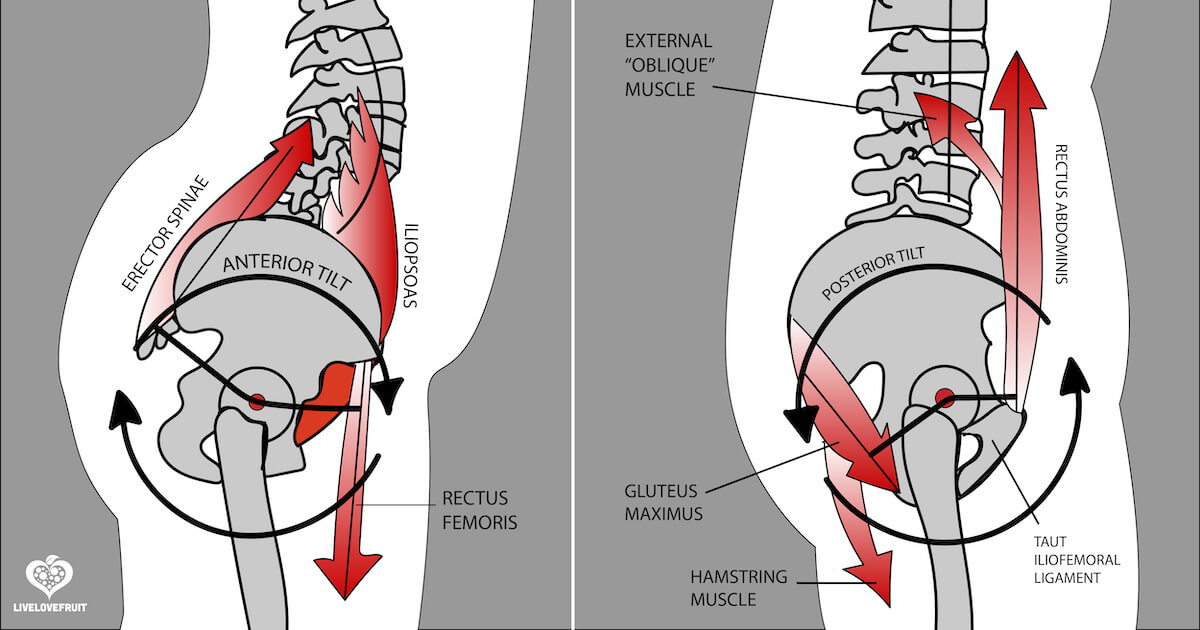

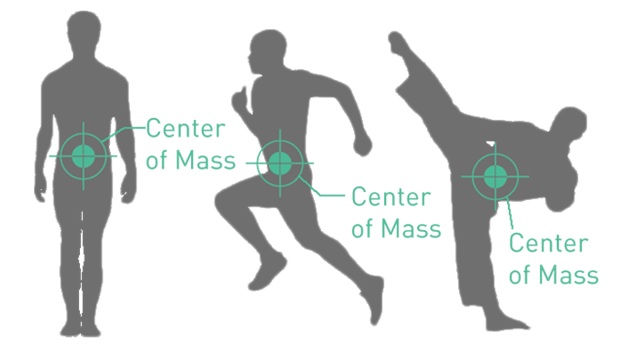

Going back to point 4 above, how do we know if your body mechanics (and thus gait) are being negatively affected by your shoes?

I’ve got a super simple 3 step system you can try right now, based on the assessing motions your body needs to be able to access while you walk (Anatomy in Motion style). I actually stole this from Gary Ward. All credit to him.

Step 1: Do the movement self-assessments and get your barefoot baseline data on how your body can move.

Step 2: Put on a pair of shoes and see if your movement assessments change- better or worse- compared to your baseline.

Step 3: Categorize your shoes based on whether they mess with your body or not and choose accordingly to your goals.

You can do this with your orthotics as well to check if they are (or ever even were…) helping you.

At first I dismissed this system because it seemed too simple. But when has over-complicating things ever helped?

Want to try it? Grab a few pairs of shoes, and check out this snippet from a little later in the shoe hangout as I take the participants through the system.

I also made a super handy workbook you can use to collect your data and categorize your shoes. Download it here.

I definitely learned something new about how my shoes are impacting my body.

For example, I learned that my favourite hiking boots actually restrict my ribcage and neck range of motion, but improve movement at my hips. And my Vivo Barefoot shoes improve movement at my ribcage and neck.

This information is useful for me to have so that I can track weird neck and ribcage symptoms (of which I have…) to whether or not I wore shoes my body didn’t like and failed to unwind with some self-care afterwards.

Knowledge is power, guys!

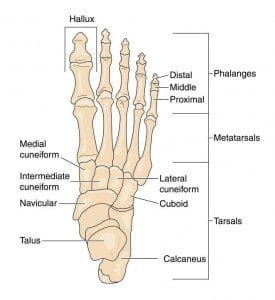

Of course there are other things to consider. Like if you have a dropped metatarsal head. Or a neuralgia. Or a bone that sticks out more on one side and rubs. Or an open flesh wound. But this is a nice starting point.

But the most important thing has nothing to do with the shoes you’re wearing…

Because if your body can’t move well, there’s not a shoe in the world that can teach your body to move differently. Only You can. And it helps to know if your shoes are in support of that trajectory, or against it. (And by “support” I don’t mean orthotics, in case that wasn’t clear…)

In addition to using my ultra-sophisticated shoe-choosing system, it is important to:

- Have strategies to proactively make your body robust to any shoe you choose, and

- Help you unwind after wearing crappy shoes.

That’s called “doing the work”.

Don’t outsource your personal power to the Shoe People

Repeat after me:

From this day forth, I am an empowered shoe-wearer. I solemly pledge to do the work necessary to become more resilient to all shoes. I will not blame my shoes for my body’s issues. I will then make informed decisions about my shoes from a place of logical reasoning.

Deal? And be OK that this might take a while. I’m not sure how long it will take me to figure out why my right foot hurts, but I’m committed to the process, and until I feel ready, imma keep wearing my slippers.

And now, because I know you’re still going to ask about minimalist footwear…

I want to tell a story about a client of mine (who will remain anonymous).

She is one of those barefoot idealists. I’m all for barefoot/minimalist shoes… I just wish my body could tolerate them.

And I wish her body could, too. But she’s in a bit of denial about that.

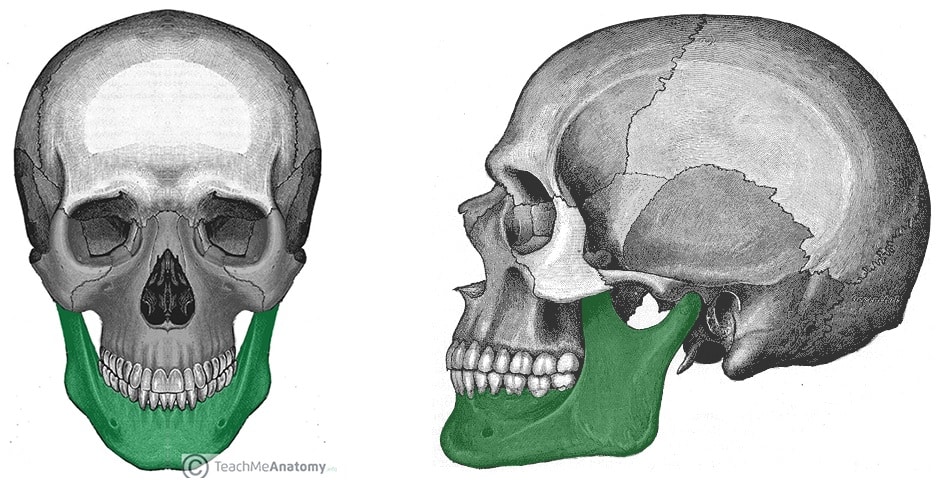

She had a pretty gnarly ankle injury when she was young, and when I assessed her, that poor foot was holding a dramatically caved in (pronated) posture, and could not supinate (create arch).

She had tried switching to minimalist shoes because she read it was the magic fix for all foot problems. I’m sure you’ve heard that rhetoric, too.

She also became one of the loudest proponents for minimalist shoes, going as far as to be a retailer of a prominent barefoot shoe company and posting videos of her doing barefoot running and hiking on her social media.

Thing is, she still had ankle problems.

After 4 sessions, we saw some nice changes in her ankle, but she asked me, “Do you think I should stop wearing minimalist shoes? Are they holding me back? Because… sometimes I think they are, but I love the idea of being barefoot”.

And my honest reply was, “Yeah they might be preventing you from making progress, and the only way to find out is to try not wearing them for a while and see what happens”.

Do you think she stopped wearing them? No…

Note that loving the IDEA of something doesn’t mean that it is something you should or can do. I love the idea of being able to eat 15 cookies everyday without consequences. But I can’t. Because that would be ignoring facts.

I haven’t seen her since, so I don’t know if she’s still having the same trouble with her body.

But what I’d like your to appreciate is that sometimes our bodies are NOT robust enough to tolerate minimlaist shoes, but maybe one day they could be.

When I tried to wear barefoot shoes, I quickly noticed that my right leg could tolerate them, but after 20 minutes of walking, all my left leg symptoms flared up.

All that to say, beware the loudest preaching people on social media, because what worked for them might not actually be working for them. OR they have some financial/emotional investment and aren’t being honest with themselves. Also, they are not you.

On the flip side, I have had a client switch from wearing heels everyday at work to rocking Vibram Five-Fingers, and noticed a huge reduction in her plantar fasciitis.

You can also check out an Instagram post recently by my pal from the UK, Helen Hall, in which she did some objective(ish) testing of how different pairs of SOCKS influenced her running mechanics , using her fancy shmancy force-plate/treadmill 3D analysis set up.

So I’ll leave you to make your own informed choices.

How to become robust to every shoe?

Ongoing commitment to getting your body moving more efficiently, and not just your feet. Because your feet have a movement relationship to every other part of your body, and without that relational harmony, a localized foot-centric exercise might not have the desired global effect.

And you’re in luck, because helping people (and their feet) move more efficiently is what I’ve dedicated my life to 🙂

A good place to start is my 4 session online workshop, Liberated Body.

I created Liberated Body to help you get to the source of your body’s problems so you can move and feel better (and wear all the crappy shoes you want).

I guide you through a step by step process to identify your body’s restrictions and give you back the movements it is currently missing.

You can participate anytime, at your own pace. Go HERE to register for the home-study (which I also help you through along the way in real time from the comfort of my couch. Thanks internet!).

Conclusions?

Just three.

- Be honest with yourself.

- Don’t believe what people say on social media about what you should do with your feet/shoes/life

- Do the work to make your body robust to all shoes and make more informed choices.

I’m here to help with #3.